By Pascal Jacob

Juglar, juglator, joculator, but also pilarius, which takes its name from the suffix pila, ball: the terminology related to the manipulation of objects, and by extension juggling, is both diverse and explicit. The generic term Joculator first appeared in a decree of the Council of Agde in 506 where it was applied to gyrovague clerics. It tends to overtake the word histrion, but it unequivocally represents depravity and lust. The notion of play, mixed with the idea of skill, permeates words with Latin, Romanesque or medieval roots, but whose common denominator remains the identification of a know-how that can provoke amazement, incredulity and admiration. From this intuitive hierarchy, jugglers draw both an imagination and effects, but they also anchor themselves in unexpected registers…

In the West, a true cultural phenomenon of his time, the medieval juggler is a steward of pleasures, but he is also a wandering vagabond with many forms of knowledge, the inevitable enchanter of stages and stop-overs, who with a trick, a tune or a jump cheers up the feasts, the wedding and the vigils... For several centuries, manipulators of words and objects, jugglers make a living by entertaining men whom they come upon during their wanderings. Their sole name carries infinite promises of pleasure, but they are also very close to the embers of Hell. In the 12th century, Honorus d'Autun suggested that the jugglers were "from the depths of their souls, the ministers of Satan". However disturbing this ambivalence may be, it nevertheless feeds the imagination of stonemasons who sculpt for eternity an entire group of street entertainers where "pure" jugglers rub shoulders with musicians and acrobats. This extremely rich interpretative statuary reflects the extraordinary diversity of the spectacular practices offered over the centuries on the construction sites of religious buildings.

A deposited sculpture, which may have come from an old church doorway that has now been destroyed, depicts a man who is half dancer, half juggler, whose attitude expresses both movement and dexterity. He throws a ball with his left hand and is about to catch it with his right hand. Artfully inserted into a crevice carefully hollowed out of the stone, it synthesises the formal elegance of the minstrel capable of astonishing the onlookers gathered to applaud him, but also and especially the creative impulse of the sculptor who saw, admired and represented him. On the doorway of Notre-Dame de l'Assomption in Maillé in the Vendée, the jugglers are perched on the shoulders of strong people who carry them.

Body images

Statuary is an inexhaustible source of references, but literature and opera, particularly through libretto, have also been inspired by the figure of the juggler for the creation of unique works. Le Jongleur de Notre-Dame, one of the short stories in Anatole France's collection L'Étui de nacre published in 1892, is inspired by a medieval story in which a simple entertainer becomes the hero of a pretty parable. In the time of King Louis, there was a poor juggler in France called Barnabé. A native of Compiègne, he went across cities and the countryside, performing many tricks of skill and strength throughout his travels. On fair days, as if to reproduce an unchanging ritual, he would lay an old worn-out carpet in the public square, thus delimiting his playing area. After attracting children and onlookers with some witty and engaging words from a very old juggler, which he never changed at all, he would take some unnatural postures, balancing a tin plate on his nose. The crowd looked at him at first with indifference.

But when he held himself on his hands upside down, he tossed up and caught up with his feet six copper balls that shone in the sun, or when, tipping over until his neck touched his heels, he shaped his body like a perfect wheel and juggled, in this posture, with twelve knives, whispers of admiration rose in the audience and the coins began to rain on the rug. After many tribulations, Barnabé became a monk and, like the other brothers, he never ceased to pay homage to the Virgin Mary. Unable to write praises or paint subtle illuminations, he slipped into the votive chapel every day and performed his tricks there at the foot of the altar... At the very moment when he was discovered and accused of insanity and sacrilege, the Virgin Mary went down the steps of the altar to wipe the sweat from his brow, thus making his daily offering as worthy as any of those presented by the other monks.

In 1717 François Couperin created Les Fastes de la Grande Ménestrandise, the third segment of which is called Jongleurs, sauteurs et saltimbanques, avec les ours et les singes ("Jugglers, jumpers and saltimbanques, with bears and monkeys"). Medieval themes were also very popular in the 19th century and the composer Jules Massenet used this distinctive interest to create the lyrical miracle Le Jongleur de Notre-Dame on a libretto by Maurice Léna explicitly inspired by the work of Anatole France and premiered on the 18th of February 1902 at the Monte-Carlo Opera House. In La Jongleuse, a novel published by Mercure de France in 1900, Marguerite Eymery also known as Rachilde uses juggling both metaphorically and literally, creating a character who juggles as much with her male conquests as she does with knives. Romain Gary also mentions juggling with balls in Les Mangeurs d’Étoiles and La Promesse de l’Aube. In 1979, the American Robert Silverberg began writing the Cycle de Majipoor, a remarkable work that is part of the fantasy genre and whose first volume published in 1980, Lord Valentine’s castle, describes aliens with four arms who are renowned as prominent jugglers…

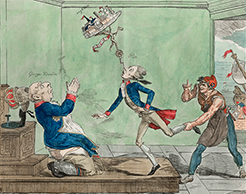

Artists impressions

Juggling can also be interpreted with humour in the caricature field. One such master, illustrator Jean-Jacques Grandville (1803-1847), portrayed King Louis-Philippe as a banquiste, standing on a stage at a fair, a feather crown on his head, characteristic of the classical decoration of squires and rope dancers at that time. The monarch, comparable to a worthy representative of the Lalanne or Franconi dynasties, is flanked by a thoughtful rooster and a colourful parrot and he handles like a virtuoso a sack of gold, the sword of Justice, a charter and some other small objects with strong political connotation. This flexibility of symbols and institutions ferociously mocked by Grandville finds a funny resonance in one of the first acts created by the Pickle Family Circus in San Francisco in the 1970s. A group of jugglers tosses about waltzing cases filled with banknotes to illustrate the secret meanders of the financial circuits with a mixture of irony and virtuosity.