by Pascal Jacob

The horse can be considered as a dramatic "apparatus" when, immobile, it served as a pedestal for Christian Müller, a circus rider who performed in Nuremburg on 18 May 1647. Apart from this, it is really the pressing need to be seen by everyone that constitutes the first solid grounds in the acrobat's decision to perch on "something," which enables him to distance himself from the ground and therefore be better appreciated by those admiring and applauding him. This choice to dominate the entourage was the starting point for the history of the immobile apparatus. It was also an elegant manner to decide on an axis, most frequently the centre of the performance space, and to use a circular movement inspired by horses. From this confrontation of mobile and immobile, an aesthetic framework arose based on the heterogeneity of forms, and the mosaic effect of the performance, which would very quickly characterise the entire circus show.

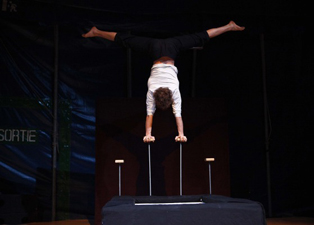

The use of an apparatus, whether mobile or immobile, simple pedestal or complex machinery, nourished acrobats' imaginations and provided unimaginable possibilities for development. In addition, it enabled several techniques to be learned, within one family or company, which could then be presented alone or in combination. Canes and balance balls, Chinese poles, free ladders, velocipedes, unicycles, wires, trapezes and fixed bars, as well as outsized accessories such as a giant glass or structures evoking the moon or clouds, composed a strange inventory, which continued to develop, to grow richer and to multiply references. The school blackboard on which Chloé Moglia writes and clings to, or the impressive metal hook suspended from Mélissa von Vépy, are subtle variations on the apparatus, or stage objects nourished by parallel influences, borrowed from every day life or monumental sculpture, but above all, they are reasons for writing and creation.