by Pascal Jacob

Acrobatics is a precise and efficient language. Mastering its skills produces strange phenomena wherein the human body yields to the constraints or demands of the apparatus. Although the first acrobats relied mainly on their extremities – hands and feet – to move, the need for more diverse feats soon arose, leading to new balancing acts on a multitude of apparatus and original structures. Jean-Baptiste Auriol, a prodigious acrobat according to the chroniclers of the day, had a reputation for being lighter than air. In the Champs-Elysées circus ring circa 1845, he performed numerous balancing acts on a tilted chair, perched atop a trident or on bottles. This performance was resuscitated by Johann Le Guillerm, with the creation of Cirque Ici. Little Huline and Gaertner, contemporaries of Auriol, also practiced these balancing acts on everyday objects, reinforcing the "magical" dimension of their exercises in agility.

Everyday apparatus

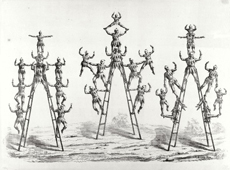

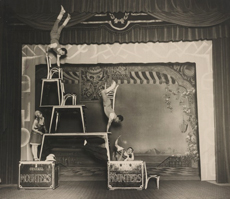

In appropriating everyday objects such as tables, chairs and ladders, there is a desire to add a dimension of simplicity and closeness to the performance. For several centuries, the Chinese acrobatic theatre worked with everyday objects from plates to umbrellas, but also with piles of heavy wooden chairs that enabled vertiginous pyramids to be built. In 1965, during a tour by the Wuhan company, French audiences discovered the chair balancing act of Xia Ju Hua, an extraordinarily elegant and precise artist. In 2001 at the 22nd Festival mondial du cirque de demain (World festival of tomorrow's circus), the balancing artist Zhang Gong Li created a sensation by building a column of chairs resembling something between a watch tower and a temple pillar, executing impressive figures as he progressed. It is the vertical aspect of the column that creates a sensation of never ending ascension and reinforces the dramatic aspect of the performance: a fascinating and frightening blend of fragility and strength that is a decisive element in captivating the audience. The chair pyramid is also a group number and acrobats, particularly the Chinese, develop clever structures from this very simple object, which sometimes have a ridiculously small base, such as the four glass bottles that support Zhang Gong Li's entire construction. A complex edifice of a dozen benches can also be balanced on the toes of a pusher lying on a trinka… Balancing act artists develop their figures at the top of these improbable scaffolds and the subtlety of the exercise lies in making the audience forget the base and look at the summit, in order to better rediscover the base during the final position and thus appreciate the extraordinary overall vision.

Balls and rollers

The juxtaposition of body-plus-object provides endless combinations and has led to the creation of a veritable repertoire over the centuries, as new disciplines are created and others merge with each other. The Rola Bola for example, invented by Français Vasque in 1898, is an unusual technique in which the artist must maintain balance on a board set on top of a roller, which creates a constant source of instability. The aim is of course to multiply the rollers and pile up the boards, which are sometimes separated by fragile stemmed glasses, therefore making the performance more spectacular. Also known as the "American roller," the Rola Bola is a small teeterboard that swings from left to right and whose axis of rotation is constantly shifting. The Chinese "Chemin de Fer" acrobatic company from the Hebei province complicated the feat by balancing a flyer on the head of an acrobat who was already balancing on top of a pyramid of cylinders.

Beyond a "simple" piling up of rollers, the discipline also lends itself to a mix of techniques: juggling or hand-to-hand, in the manner of Russian duo Legostaev and Bougaitsov, who developed characters and comical situations during their act. The wooden or plastic balance ball of variable diameter is another factor of instability, especially for jugglers. Rogana, Alexandra Pauwels and Alessandro Medina have all played on this additional effect to increase the level of difficulty and create a unique universe in which the ball is both a support and a vehicle, as well as a pretext for creating a poetic universe.

Ladders and instability

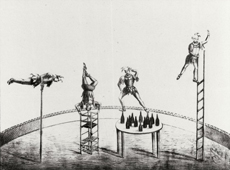

The free ladder, made from wood or metal, is one of a number of everyday apparatus that were used in street games before being transformed into circus techniques. Daniel Cyr, Franck Pinard and Simon Nadeau have fun with this chronically instable device, transforming it into a skill and using the ladder as an uncertain, rigid partner. Maintaining balance by moving the hips, the acrobat can balance or climb up and down an object whose simplicity makes it all the more fascinating.

The mobile structures created by the stage designer Raymond Sarti for Vita Nova, the show performed by the 1999 graduating class of the Centre National des Arts du Cirque in Châlons-en-Champagne, led to unique balancing movements suggestive of the fascinating confrontation between a flexible body and a rigid piece of apparatus, which is a source of inspiration for numerous contemporary acrobats.