At the roots of circus and dance

by Marika Maymard

Circus and dance have long shared a certain number of influences, and their respective histories sometimes borrow from the same sources. Stemming from imitation rites forged by primitive hunter-gatherer societies, postures and figures gradually distinguish the two disciplines over the centuries.

Symbolically, history very early on associated choreography with acrobatics. In this regard, the jump brings acrobats and dancers closer together, while also acts as a dividing line between them. It also symbolizes how the two, theoretically different disciplines might be similar in their respective developments, mainly in terms of the spectacular and performance. The circus and ballet share a certain number of technical elements, but skill blossoms differently in accomplishing phrases and sequences.

The Grands-Danseurs et Sauteurs du Roy (the Great Dancers and Jumper of the King), founded by Jean-Baptiste Nicolet, comprised actors, dancers and agility artists in equal numbers. The quality of this company enabled it to obtain a royal privilege in 1772, and thereby become incredibly famous, which would later lead it to oppose Astley's innovations when the latter wanted to establish his jumpers and circus riders in Paris.

In the 18th century, both circus and dance drew partly on the fairground for inspiration. Above all, they used rope dancing and balancing on points, a discipline and a technique that would contribute to the development of a new language in the ring and on stage. When the modern circus took shape in London from 1768, it regularly absorbed other artistic forms and appropriated postures and attitudes that were quickly transformed into performance codes, which seemed to have always belonged to it. The best example is probably the annexing of the ballerina figure, transplanted into the circus ring, perched on a horse: in 1832, Marie Taglioni created the role of the Sylph, and for the first time in the history of classical ballet, wore a long frothy skirt: the tutu. Inspired by the success of the dancer, the circus riders adopted the same costume and transposed key ballet scenes to the panneau – a flat saddle. The assimilation was instant, and for more than a century, the tutu identified the ethereal figure of the circus rider, but was also worn by rope dancers and tightrope walkers, who thereby created another direct analogy with the initial model.

The term rope dance is unequivocal, and the repertoire of steps and jumps is the same: variations, adagios, lifts, pas de deux, and quadrilles are terms shared by dancers and tightrope walkers, but several of these technical terms are also used by acrobats. Adagios and lifts identify in particular, certain forms of hand-to-hand, and the pas de deux had also been a part of the circus riders' repertoire since the 19th century.

Beyond these acknowledged influences, it is evident that dance has permeated acrobatics since the 18th century. Influenced by the development of light musical and choreographic forms, such as the burletta, or Cachucha, many circus acts are based on dance, whether acrobatic, serpentine or character, while equestrian revivals and quadrilles have been part of travelling companies' repertoires since the first half of the 19th century. Dance nourishes and influences circus transformations, helping to make acrobatic sequences more fluid, smoothing out inevitable rough edges with sequences of complex movements, and softening the austerity of pure technique. Finally, in the same way as stage productions, horseback or rope dancing serves the narrative.

From the 1930s, dance helped to physically and artistically transform generations of Soviet acrobats, influencing the writing and choreography associated principally with the creation of prodigious aerial ballets: The Cranes, choreographed by Piotr Maestrenko on the aerial bars. The combination of these two practices lies behind the development of a unique aesthetic that characterizes Eastern circuses, and is a way of underpinning the acrobatic performance by making it elegant and fluid.

From dance to circus and back again

by Odile Cougoule

In the early 1960s, dance was still classical in performance and potentially bourgeois and the rules were established in conformity with tradition. Arabesques, attitudes, turns in the air, splits and pirouettes: the vocabulary that described it was characteristic of the attention paid to the search for brilliance and beauty, masterful execution and a quality of performance that saw a hierarchy established between artists. Similar criteria operated in the circus world.

Dance paved the way for modernity.

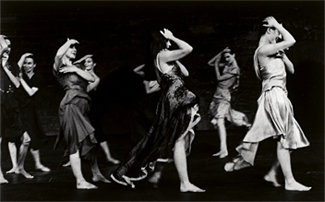

But the transformations that shook up society at the time provoked a more open attitude to the world. Artistic exchanges were numerous and now nourished the debate on art and how it should be presented to audiences. For dance, there was, on the one hand, German expressionism, which advocated an internalization of movement. Led by Mary Wigman in Gemany, This movement was developed in France from 1958, by those who were known as "the pioneers": Françoise and Dominique Dupuy – a former Cnac teacher – Karin Waehner and Jacqueline Robinson. On the other hand, lay the supporters of abstraction, who wanted to rid movement of any sensation or affect. This line was defended by the American post-modernists such as Merce Cunningham, who came to Paris in 1964, Lucinda Child in 1972 and Trisha Brown in 1974. These powerful and radically opposed influences led the generation of dancers who came of age with May 1968, to address the issue of meaning beyond form. This questioning liberated them and enabled them to free themselves from convention, to flout the "prima ballerina," and to abandon the argument for classical ballet as a support for creation, going instead in search of inspiration in concepts, experimental movement, and everyday gestures.

Contemporary dance and new circus: a shared state of mind

Shaking up accepted thinking on art would soon spread to the circus universe, where everything was still to be invented. Companies such as Archaos and Le Cirque Plume, who from 1980, cemented the arrival of the "new circus," relied on other art forms to reconsider the circus show and the idea of the "act." They did not hesitate to look to choreography for concepts and tools for renewal. Initially, the performance was based on the new freedom acquired by dancers. For Archaos, for example, the body itself carried meaning, and its presence on stage should no longer suggest, idealise, dazzle or provoke dreams, but rather, should disorient, and have an "impact' on the audience. Just like dance, which invited the everyday into performance, Pierrot Bidon – who founded Archaos in 1984 – initiated the circus renewal by mixing genres and people. He favoured culture shocks and provoked the audience upon their entrance, with a big top filled with motorbikes, lorries and stock cars on fire, in Métal Clown (1986). The act now became part of a grand contemporary epic that told of today's world and its men, in a staging that eluded the traditional sequence of exploits, which highlighted this or that artist. The atmosphere and the collective took precedence.

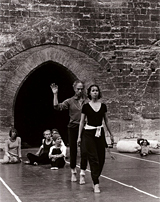

Freedom, danger, and audacity set a new dynamic in motion. The circus was hungry, and happily ingested the other disciplines, and dance – a generous form – which took an interest in any body in motion, also acquired a taste for danger. Choreographers and dancers then began to collaborate regularly with circus artists. Educational and artistic orientations defined between 1990 and 2002, by Bernard Turin, for the Cnac (national centre for circus arts) in Châlons-en-Champagne, went along with this movement. Josef Nadj was commissioned to direct the school's graduation show for the class of 1995, which confirmed this obvious relationship between dance and circus. Thanks to the famous choreographer's powerful proposal, it also enabled the circus show to acquire the status of an oeuvre.

Le Cri du caméléon (1995), inspired by the writer Alfred Jarry's universe, and in particular his novel The Supermale, gives power to the imagination for an hour. A theatrical performance, comical situations, humour, exploits, bodies, music and costumes are all treated equally in the service of the performance. The ten boys who perform on stage provide a strong but sober physical presence, which is not based on prowess, but on a capacity for creating tension, and attracting the attention of the audience simply through physical performance. The artist is entirely involved in the show – body, heart and mind. The unusual relationship built during this work between movement, space and time –dance fundamentals – is particularly visible in the sequence that I shall call "group juggling with hat, on chairs and walls."

Hats, which are a leitmotif in the dramatic art of this sequence, circulate from hand to hand and head to head, without being imposing to look at: we are in the thick of a juggling act without however, being within the circus juggling mechanism. There is no narration, but a game with the imagination, using the body as mediator.

In 1999, Vita Nova followed. This show was created for the 1999 Cnac class, and the choreographers Héla Fattoumi and Éric Lamoureux approached it with these words: "Everything is there, contained in these fragments of "raw material" with such remarkable texture. Putting these raw materials to work means not rushing in to give it meaning." These "Fragments" were the numerous disciplines that the choreographers had to deal with. Earth-sky: the physical performance was set up in this in-between space, drawing on dance for the vitality provided by the principle of the "tense-relax " movement, by giving the space a role as narrator, and also by accepting the dialogue with music. The phrasing of the dance finds its place, and beautiful sequences unfurl, such as the floor acrobatics sequence that begins with swaying, running movements, whereby nothing other than the journey of the body in space appears, as the organisation of space and time create movement. Shifting weight from one part of the body to another, or shifting the weight of the entire body in the space, injects the tempi, defines encounters, and shapes individuals who are ready for their acts. For the acts are there, as is the "finale," in the shape of an astonishing flying trapeze trio.

These experiences provided the impetus to this young generation of Cnac students, persuaded that now, they had to be daring enough to cross disciplines without fear of losing their specific skills. João Paulo P. Dos Santos invited the Portuguese choreographer Rui Horta to work on Contigo, a Chinese poles solo created in 2006 for the Avignon Festival (SACD/Le Sujet à vif). It demonstrated a magnificent physical dialogue between man and pole, owing to very subtle placing work, slowness, and fall and recover work.

Circus: from the exploit to listening to one's body

The circus world is harsher than that of dance, as the body is constantly faced with risk. However, appealing to it for something other than efficiency and productivity is possible. In the long term, the meeting with dance will definitely help develop a body that is skilful in more subtle ways. Thierry André, the founder of La Compagnie de l’Ébauchoir and a juggler trained at the Cnac, said for example, "moving forward through the life of objects with your fingertips." He was talking about his solo, Petite Pièce issue du cirque (1996), in terms of music, physical harmony and balance, and affirmed that: "movement is invented in time and space." Feet on the ground and head in the clouds – in reference to the dual direction that is the support for dance movement – the central body initially seeks to sculpt space and play with time with every action. Throughout the piece, the relation between body and object gradually takes priority over the juggling feat, and yet the clubs themselves move in three dimensions, passing each other, corresponding to each other, but are then forgotten in favour of a poetic and musical dance. Stéphane Ricordel and Olivier Meyrou seem to possess both the efficient circus artist's body and the sensitive, dancer's body in Acrobate (2013). Placements, pre-movement, centring, flight and fall – this was organic contemporary dance seeking a precise intention in physical movement and the artist's emotional intelligence, to bring movement to life. The circular sequence alternating jumps, falls to the ground and acrobatic figures, showed what this internalization of movement, leading to meaning, was capable of.

For Nos Limites (2013) Matias Pilet and Alexandre Fournier asked choreographer and director Radhouane El Meddeb to guide them in their research on prevention, a lack of mobility, and impossible verticality. Their duo shows subtle knowledge of the mechanics of movement recalling the effects, in dance, of the functional analysis of the body in a danced movement, but also of a benevolent way of looking at the body. Tender or sharp body-to-body movements and lifts performed wholly on the ground show a sequence of flight-suspension-falls that is performed with specific awareness of the role of bodily weight, which enables this "in-between" state, where the quality of the movement is decided. The body's texture is changed by this experience. We are beyond skill and technique, but in the most spot-on interpretation of what a meeting between two bodies is founded on: shared weight. This exchange from one to the other is visible, and moving in the trust that the performers have in each other, and it sets the tone for the performance without having recourse to any dramatic artifice.

This work, which uses the body and its weight in transfers of weight pushed to the extreme, evokes Bambou de souffle (2006) by Bruno Krief and Armance Brown, who took an abstract approach. Their creation was motivated by the exactitude and cleanness of the body in movement, and technical perfection. Refusing exhibitionism, they endeavoured to feel every proposed movement by forgetting formal habits until they found a state that would make sense. The body became the sole leitmotif of the show, and constructed the dramatic art through its changing states. In this spirit, we can also cite Appris par corps (Un loup pour l’homme company, 2007) by Alexandre Fray, a pusher, and Frédéric Arsenault, a flyer, an act combining Icarian games and hand-to-hand, and in which they are both wonderful dancers. In addition there is Offrande (2010) by Marie-Anne Michel, who led "explorations on a pole – in mid-air."

For both dance and the circus, techniques are development through confrontation with other bodies and this lies at the heart of the disciplines' modernity. The performing arts, whether circus or dance has made the most of this sometimes muddies the waters… Is it circus? Is it dance? The osmosis between the two is such that it is sometimes difficult to answer that question. But after all, should it really be answered?