by Pascal Jacob

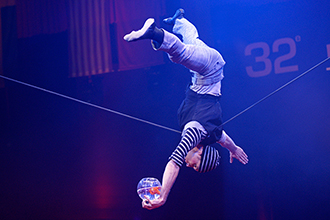

By juggling upside down, as if suspended from the theatre ceiling or hung in the dome of the big top, the artist modifies the perception of the gesture and introduces a new technical density. Even if the manipulated objects are light and seem more likely to float than to fall, they illustrate another approach to juggling, both fluid and contradictory.

The Canadian Kai Leclerc and the Circus Oz troupe from Australia have incorporated this practice of inverted or upside-down juggling into their shows, inevitably causing spectators to be amazed.

The questioning is interesting since it raises the problem of another materiality of the manipulated object while challenging the notions of balance and stability. The Russian wire artist Andrei Ivakhnenko multiplies the difficulties by combining juggling on a unicycle while balancing on a wire. Conceived in 1995 by director Valentin Gneushev, the act combines humour with technical virtuosity while symbolically stigmatising the AIDS virus by having the artist wear a blood-red suit with spikes as a support for his accessories. Andrei Ivakhnenko juggles with canes bent at their ends and uses the spikes that scatter his outfit, including his hat, to hang them up, take them back…

Balanced juggling, like the principle of composition, has now become more of a one-off element in a show than a pretext for writing a full number. This is a significant shift in the meaning of prowess, long considered self-sufficient

The Collectif AOC has integrated balanced juggling sequences on several occasions, notably in 2005 in the show Question de directions, with a highlight of club manipulation combined with trampoline and trapeze movements, but also in 2009 in Autochtone, a show choreographed by Karin Vyncke, with also a great passing of clubs between a trapeze and jugglers on the ground. In Bascule, created by the Anomalie company in 2005, a passing of clubs also between two trapeze artists illustrates this mutation of effects.

The dramatisation of a performance takes on a particular meaning in the creations of the Norwegian juggler Frida Odden Brinkman, trained in Sweden and at the Académie Fratellini. She precisely inserts juggled fragments into a framework developed from a space and the elements that occupy it. By using a wire as the median structure of her playing area, she creates an interesting second level of perception for the spectator while using it for a bouncing or aerial juggling sequence. Another Norwegian fan of the flexible wire, Christer Pettersen, manipulates an aquarium and its occupant with flexibility while he controls the fluidity of his balances

In fact, what now characterises this singular discipline is probably the assumed fragility of a very intuitive fusion between the stable and the unstable in the service of a purpose. Less demonstrative than before, balanced juggling has become the pretext for the creation of moments of pure virtuosity, as a counterpoint to a narrative tale.

This is the challenge of OPOPOP's Le plus petit Cirk du bord du bout du monde, a show that is entirely staged on a three-metre diameter ring, a flat surface of a rudimentary cone placed in precarious balance on a rock. The stage object oscillates, sometimes seems to dance under the impulse of the wind or the imbalance caused by a body too heavy on one of its edges... The juggled moments follow one after the other, from the most classical to the most uncertain, from a dorsal manipulation of rings to the breath that makes a feather always in balance tremble on the tip of one foot. Balls, parasol and floating silhouettes are the devices and elements that make up the framework of a pattern of juggling that can explore the balance and imbalance that have been developed as a poetic and technical language.