by Jean-Bernard Bonange et Bertil Sylvander

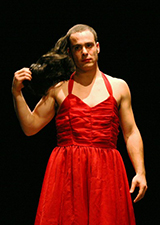

The mediator clown or social clown, heir to the buffoon tradition and the red-nosed Auguste, has occupied for about thirty years a prolific position on the well-ordered grid of social reality by opening a playful fictional space where people live, work, receive treatment and heal, suffer or meet each other. We can consider this to be a modern resurgence of the variety of comic and offbeat characters who occupy a special place in human societies.

Anthropological landmarks

Researchers in different fields agree to identify the characteristics of these "deep resonance entertainers" (Martin1) present in many societies and periods of history. This succession of comedians demonstrates a profound artistic and social inventiveness in a parodic, critical and regenerative playing register that the social intervention clown seems to have inherited. He returns to the traditions of the improvising actor in contact with social life and whose security lies in the appearance he will give to his character: it is the mask of the clown, in other words all the signs of clown art, which protects the actor's person and at the same time sets the clown's performance free.

Ritual comics

Ethnologists have discovered comic characters on different continents that provoke laughter during ritual ceremonies. They are sometimes called sacred clowns in reference to European clowns2 or sacred buffoons or ceremonial buffoons.

They are "ceremonial characters whose strange costumes and rude jokes make the audience laugh". They have been likened to the Tricksters, mysterious mythical characters who have a function as "imaginary violators of taboos" and "are the revealing agents of a fundamental, contradictory experience that generates dramatic situations. " (Levi Makarius3)

The King's Fool

In the Middle Ages and during the Renaissance, the Fools occupied a prominent place on the comic scene with the authorities. The King's Fools have gradually become professionals in entertainment, laughter and irreverence, as much as the clowns in the ring are nowadays. They can be considered as the ancestors of the social intervention clown. In this system, the questioning of power involves the mediation through play and the convention of the buffoon's madness, "this prototype of the clown on the borders of wisdom and madness, the tragic and the burlesque, the sublime and the derisory" (Simon4).

These characteristics will remain relevant in the evolution of the clown from the 16th century until today. On the stage, in the circus, in a professional meeting or in a hospital, the clown is therefore, in the original sense of the word, an eccentric.

The renewal of irreverence

During the 20th century, the work of the "red-nosed clown" became one of the foundations for training actors. Founded in 1956 in Paris, École Lecoq has created a new working approach called "in search of your own clown" that has left its mark on many creators in the performing arts. This orientation was then developed by companies combining artistic training and a demand for authenticity – such as the Bataclown from 1980 – in workshops, open to actors and non-actors (Augusto Boal5) with the requirement to base the character's excellence on the actor's authenticity (Bonange, Sylvander6).

This renewal of the clown's work is part of the socio-political context of the 1970s, with a desire for freedom that exploded the stranglehold of social conventions and highlighted a political criticism of the ideological function of art and theatre. We can mention Jérôme Savary's Grand Magic Circus or Ariane Mnouchkine's Théâtre du Soleil, the Living Theatre, the Bread and Pupett, the Odin Theatre... These companies used the work of the body and political and social criticism as the basis of their theatrical language. The questioning of academic dogmas and social elitism blurred the boundaries between theatre, politics and psychology, between dance, mime, theatre and circus, between voice, body and imagination, between mythologies, stories and dramatic repertoire.

The clown appears as the figure of this transversal profusion of disciplines where many street theatre companies have appeared but also comedians or clowns such as Raymond Devos, Bernard Haller, Coluche, Rufus, Les Macloma, Jango Edwards... or even clown companies performing, in particular, in specialised festivals. One of the first in France - the Festival clown de Montorgueuil - assembled in January 1980 Les clowns du Prato, Motusse and Paillasse, the Klown Kompagnie, the Cirque Théâtre d'Alberto, the Bataclown…

This development of the theatre clown has continued up to the contemporary circus and in the circus artists' training programmes. The social intervention clown is a resurgence of irreverence and transgression in a conservative and well-meaning society. At the same time, the provocative humour of singer-songwriters and caricaturists, where great precursors have distinguished themselves, from Pierre Dac and Francis Blanche to Boris Vian and Georges Brassens! Anne Ubersfeld7 notes that the buffoon has left "history" to join "the theatre". After the disappearance of the buffoon under the absolutism of Louis XIV and subsequent prohibition under the empire, the social intervention clown became in the 20th century a new figure of the King's Fool. He came back "into history".

1. Serge Martin, Le Fou, Roi des théâtres [1985], L'Entretemps, Collection Les voies de l'acteur, 2015.

2. Most of the work of these ethnologists took place in the early 20th century, at a time when the circus clown was reaching its peak.

3. Laura Levi Makarius, Le sacré et la violation des interdits, Payot, 1974.

4. Alfred Simon, La planète des clowns, La Manufacture, 1988.

5. Augusto Boal, Jeux pour acteurs et non-acteurs. Pratique du théâtre de l'opprimé, La Découverte, 1991.

6. Bertil Sylvander, Jean-Bernard Bonange, Voyage(s)s sur la diagonale du clown. En compagnie du Bataclown, L'Harmattan, 2014.

7. Anne Ubersfeld, Le roi et le bouffon, Corti, 1974.