by Pascal Jacob

By naming one of his works Les Compagnons de l' Oubli, a bronze piece depicting a standing bear and its trainer, the French sculptor Godefroid evokes the strange complicity that has united Man and the wild animal since time immemorial. The animal is powerful, totemic and as revered as it is feared. It is therefore a question of a balance of power, a history of domination and acceptance that transcends borders and cultures: bears dance and imitate human beings, from India to Turkey, from the Carpathians to Italy, from the Eastern borders to the Western frontiers.

Brown, black or white, sloth, Malay or polar, small, imposing or colossal, spectacled or collared, the animal comes in various shapes and colours from one continent to another, but its dangerousness varies little. Although the West initially attached itself to the breed within its reach, the brown bear that had been haunting ridges and forests since the 19th century and the development of the animal trade, almost all bears were considered suitable for dressage and became part of the large catalogue of circus animals. Heroes of numerous engravings, the bear is with the monkey and the dog the best partner for the performers who roam around the world. One of these plantigrades dances in the film of Marcel Carné's Visiteurs du Soir, a film with medieval connotations, but which is a good illustration of the permanence of the trained bear through the centuries. Painted, embroidered, sculpted, the animal is part of a mythical bestiary where its natural charisma is the source of many legends. Big and strong, the bear offers both a silhouette and a symbol to adorn banners, coats of arms and decorations. Doesn't the Berlin Film Festival give a Golden Bear to its prize-winners, while the city of Bern has made it its emblem to the point of holding some permanently on its soil in a pit that is now covered with vegetation?

The other beast

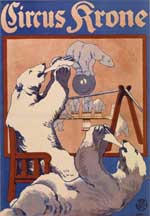

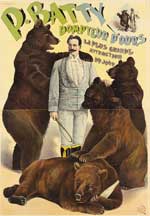

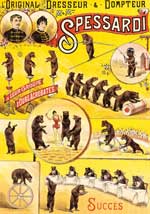

It is the fairgrounds that will ensure the transition between the public squares and the ring. The Pezon dynasty was notably developed by training wolves and bears. Most of these establishments owned one or more bears, presented as a counterpoint to the tigers and lions. At the same time, the circus quickly offered itself as a new territory to allow all bears to demonstrate their ability to learn a series of tricks that were thought to be the preserve of other, more skilled creatures: Riding a bike, riding a motorcycle, skating, walking on a ball, but also propelling a man by jumping on the tip of a seesaw, climbing on a trapeze, riding a horse, or juggling are part of the repertoire of bears that have been trained for a few decades. While the brown bear has long remained the most common bear because it was easy to acquire, with some trainers not hesitating to fetch them themselves in the mountains, the polar bear was quick to steal the spotlight as soon as its native lands were approached and occupied by regular capture expeditions.

However, although brown bears have often been presented alone, polar bears were quickly introduced in large and small groups. With 70 animals gathered in a single cage in 1870, the German Hagenbeck has undoubtedly created a record that will remain unparalleled, but he also inspired his competitors and the first half of the 20th century saw the development of a very clear taste for acts designed for about ten or fifteen animals presented in the central cage. In fact, this is another notable difference: brown bears are very rarely presented in a cage, whereas the polar bear, save for very rare exceptions, always is. In France, the trainers of Turkish origin Edda and Kemal owned one, trained with three other animals of different size and colour, and showcased at the end of a leash... The imposing animal turned heads and generated excitement when it appeared on the arm of its trainer, a colossus that looked tiny compared to its partner with immaculate fur. The East German trainer Ursula Böttcher caused the same sensation when, 1m60 tall, she directed her group of polar bears whose star, the giant Alaska, terrified the spectators with its three metres of muscles, claws and fangs as he leaned towards the frail young woman.

Roles and partners

The Russian trainer Filatov specialized in training these animals by creating in the 1950s his Cirque des Ours, a series of scenes based on a group of about forty animals able to complete and fulfil the second part of a show. Attached to a troika, boxers, cyclists or acrobats, Filatov's bears perform "alone". Behind the scenes, they complete their work in a perfectly tuned routine, crossing the curtain in turn to return at the end of their respective performances. This principle, innovative in its time, contrasts with the Western ways of presenting bears, where bears are all in the ring and perform when the trainer requests them to do so.

The cinema has also taken advantage of this mythical animal by producing numerous films where it is the main star: from ‘Winnie the Pooh’ to ‘Baloo’ for the animated films and ‘The Bear’ from Jean-Jacques Annaud, without forgetting the 1960s series ‘Gentle Ben’ where a Baribal bear is a young boy's playmate and adventure buddy.

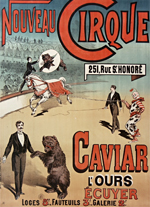

Today, although bears still dance in a few public squares in the Middle East, they have virtually disappeared from the circus rings and are no longer part of the European circus tents programme. For Battuta, a show of the equestrian theatre Zingaro inspired by the gypsy world, the master horseman Bartabas had fun by hiding one of his riders in a natural and truer-than-life bearskin to create the illusion for a lap around the ring of a wild animal able to match his acrobats. This false bear was reminiscent of the one who had contributed to the success of the Nouveau Cirque, the one named Caviar, a virtuoso squire drawn by the poster artist Jules Chéret and whose effigy was displayed on the walls of Paris. More recently, Madrid's Circo Price offered its Christmas audience a performance of polar bears... created from scratch by Andrea Mella, skillful puppet builder: these amazingly realistic animals, animated by acrobats experienced in animal imitation, have managed to fascinate as much if not more so than their living models.

It is perhaps a decisive step in the necessary acceptance of an inevitable disappearance, a way of constructing another relationship with curiosity and exoticism, two pillars of a circus steeped in conventions and thus perfectly timeless.