by Pascal Jacob

As early as the 18th century in the ring of the Astley Amphitheatre, an equestrian attraction blends the equestrian equilibrium of an elegant female equestrian standing on the back of a horse with the progression of a swarm of bees, trained to transform itself into a vibrant armour, both moving and enveloping at the same time. Created by beekeeper magician Daniel Widmann, whose authoritative treatise Philip Astley will publish in his day, the performance is revived on horseback by Martha Mary, known as Patty Jones with extraordinary success. The horse is protected by a thick caparison to protect it from a possible sting, but with her face uncovered Astley's young wife gets two swarms to swirl around her a few times until they finally head towards some baskets filled with flowers and sugar.

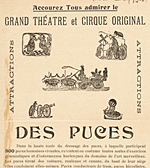

This fascination for the tiny, strange counterpoint to the power of horses, will offer many trainers new possibilities to arouse the curiosity of the public from the 19th century onwards. One of the best-kept secrets is undoubtedly the one concerning the training of fleas, a speciality that is more for the fairground than the circus, but which continues to fascinate spectators.

The presentation of these very small animals is traditionally done under a good size magnifying glass and their "prowess" is essentially a set of subterfuge to create the illusion of dressage which is obviously impossible to achieve. Delicately harnessed, hitched to tiny cars, the fleas try to escape, and their jumps pull the vehicle over short distances... Aside from these "cooperative" insects, scorpions and mygales are added in another category of exhibition. These are worrying creatures whose activity is limited to walking on torsos, shoulders and hands under the watchful eyes of the delighted and frightened spectators.

Crawling

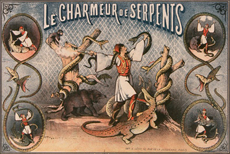

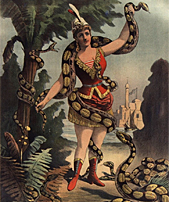

These animals belong to a singular category, the one that plays on fear and worry rather than on the admiration aroused by the elegance of the equestrians and the flexibility of the acrobats. When Captain Wall's one hundred crocodiles enter in successive waves in a circus ring, this sea of scales, these powerful scents, terrify the public, even more easily as there is no real barrier between the saurians and the audience. The entire prehistory suddenly comes to life in a setting saturated with velvet and gold, and from one end to the other, it gives rise to some frightening thrills. These animals from another age are often accompanied by other reptiles, pythons, boas and varans, which are listed to varying degrees in the catalogue of human phobias and are considered to be powerful fear and horror triggers.

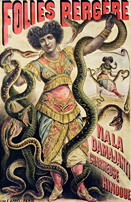

The snake conveys the myth of Eve, perhaps symbolically the first trainer in the history of mankind, a figure incarnated for a brief period on the stage of Zumanity, a Cirque du Soleil show created in 2008 in Las Vegas with two magnificent pink pythons wrapped around the body of a lovely acrobat... This closeness between the animal's supple and warm skin and that of the charmer, a detached expression of the Medusa and the goddess Cybèle, is magnified by a dresser like Rosita Rayas, an artist who associates the mastery of her animals with a very elegant presentation.

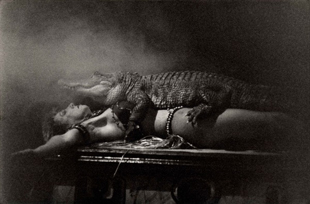

In the 1930s, strange attractions fascinated spectators from Europe and America: a young woman with exuberant hair gets into a cataleptic state, gets stones broken on her stomach, manipulates huge snakes and hypnotizes her two favourite alligators. Born Renée Bernard, from Bordeaux, Koringa (1913-1976) owes her stage name to Bertram Mills' showmanship, who was enthusiastic about her feats of fakirism and anxious to pay homage on the posters to the mysteries of the Indian Empire. Koringa seems to have been the assistant of Blacaman, an animal charmer from Italy, but capable of embodying a Hindu fakir who looked and sounded the part, as comfortable with wild animals as with crocodiles, especially at the Hagenbeck-Wallace circus. Koringa performed in France in the 1950s, in Paris and on tour, notably with the Cirque Pinder in 1956.

Frights

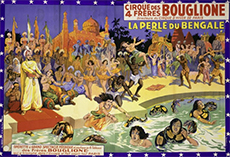

To conclude his performance, Captain Wall brings a large aquarium mounted on wheels and he dives in with two crocodiles, a feat reinvented by Tina Rosaire in the 1950s under the big top of the British circus Chipperfield and adapted by the trainer Karah Kavak on stage at the Moulin Rouge in the 1990s. When the Bouglione brothers created La Perle du Bengale in the 1930s, an exotic pantomime with many of the animals from their menagerie, they could not resist the idea of using the Cirque d' Hiver swimming pool for an astonishing scene: young women thrown to the beasts for the sake of history, swimming among huge snakes and conveniently disappearing in frightening swirls.

This dimension, triggering pure anguish at the idea of a fatal calamity, is the same as the one produced by a terrifying attraction presented by an Italian circus in the 1980s. A curtain masks a glass tank filled with piranhas: a very undressed young woman slips into the midst of the ferocious carnivorous fish without hesitation, shares their space for several minutes and springs out of the basin without the slightest scratch. The room still holds its breath when an imposing piece of meat is thrown to the piranhas who, of course, hurry to devour it.

Insects, reptiles and carnivorous fishes are obviously animals that appreciate each other at the margin of the history of dressage, taming and immersion, but they also ensure an effective link with the fairground dimension of the circus, a form of unexpected anchoring in the long history of phenomena and exhibition that continues today in very contemporary and punctual quotations like the troubling black feather bath of the Grimm show by the Cahin-Caha company (2003).