by Pascal Jacob

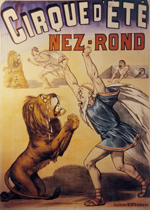

When the curtain rises on the Théâtre du Cirque Olympique on Thursday 21st April 1831, the expectations are immense: for the first time, "fierce beasts" are offered to the public's admiration in a different environment than the smoky and dark atmosphere of the menageries. They have become acting partners, or even "actors" as such, alongside cautious performers and their omnipresent tamer.

The outline of Lions de Mysore is only a pretext: according to the frontispiece of the play, it "has been arranged to properly place the animals trained by Mr. Martin". The point is clear, but it is no less intriguing. The wild beasts of the first tamer in modern history only appear in the second act, but the reaction of the spectators confirms to the promoters of the show that there is indeed a beautiful opportunity to exploit. Zoological coherence is seriously compromised by the presence of two lamas and a kangaroo, but the time has not yet come for factual accuracy and the novelty of the genre seduces the public with its good-natured exoticism and especially the very real presence of wild beasts in the flesh with their claws.

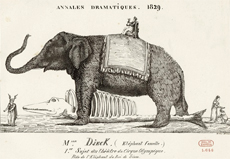

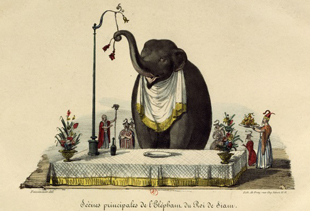

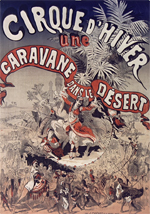

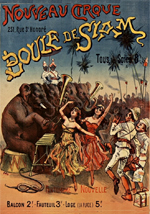

Lions de Mysore opened the way for a unique type of show, the exotic pantomime, a theatrical form that replaces the military reconstructions to the glory of the Empire that had dominated the Olympic Circus until the fall of Napoleon I. If ten years earlier, L'Eléphant du Roi de Siam, a play in three acts and nine parts, was created on the 4th of July 1829, already as a pretext to integrate Melle Djeck, M. Huguet's Asian elephant for an obviously spectacular scene, the presence of the pachyderm is a precursor above all when it comes to exotic pantomimes which will soon follow with ever more numerous wild beasts.

Martin is a skilled trainer, but Van Amburgh and Carter, respectively American and British citizens, capitalise with their different personalities on the success of the French trainer's exhibitions. Van Amburgh arrived from London where he had triumphed in the pantomime Charlemagne and settled in the Porte Saint-Martin theatre with all his menagerie. In an attempt to keep the audience on their toes, La Fille de L'Emir is performed after a vaudeville, but the audience, galvanised by the roars and smell of the wild animals held behind the scenes, heckles the actors who must leave the stage before the end of the play under a rain of apple wedges and pits while the crowd shouts "The beasts! The beasts!". When the canvas finally rises on Van Amburgh, a silence that is both frightened and respectful replaces the screams: the tamer is supposed to play a character, but it is the presence of a lamb beside him that fascinates the audience. In London, for the purposes of the plot, he entered the cage with a little girl: in Paris, it is a small wooden and fabric model who plays the role, but the wild beasts are very real! The triumph lives up to expectations: the writer and columnist Théophile Gautier turns it into a serial that is closely followed without skimping on superlatives and allusions: "Never did Talma's entrance, even Hamlet's, where he arrived backwards, pursued by his father's shadow, produce as much effect as Van Amburgh's, all chests were gripped with anxiety, blood flowed back to each and everyone's hearts." (![]() read futher)

read futher)

On the 1st of October 1839, James Carter took to the stage of the Olympic Circus to play the Bedouin Abdallah in Le Lion du Désert, a play in which he faced tiger, lion and leopard as a counterpoint to a very thin plot, but in which the authors nevertheless made sure to cut out his tongue since he did not speak a word of French! Carter is no worse than Martin or Van Amburgh, but the public is already getting tired of these somewhat forced exhibitions and critics are laughing at the docility of the wild animals: by calling them ferocious, Buffon was obviously wrong because with Carter, he says, "a huge tiger and a colossal lion suffer from the treatments that the most family friendly cat and the best trained poodle wouldn't suffer from." (![]() read Théophile Gautier)

read Théophile Gautier)

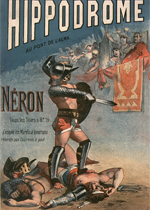

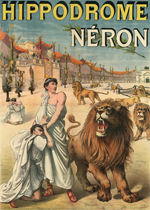

The vogue for these wearisome creations, where only animals ensure success, is quickly running out of steam. In 1891, as an attempt to revive the spirit of these successions of living scenes, Neron's fourth revival at the Hippodrome de l'Alma, to the music of Edouard Lalo, made its mark as a spectacular fresco where wild animals were invited for a scary sequence. The roaring lions tear apart mannequins made with meat wedges, creating striking images in the light of torches, but despite this bloody reconstruction, a brutal counterpoint to other sequences that were more evocative of Roman grandeur, the enthusiasm of the French public is no longer the same....

From now on, the wild beasts are enough on their own and will gradually constitute a simple number inserted in a show where squires, acrobats and clowns cohabit. In Germany, however, pantomime continues to be popular and the troupes of the Renz or Busch circuses maintain this tradition of the animated fresco by occasionally incorporating the most exotic creatures from their menageries. On the 13th of May 1900, the creation of Vercingétorix on the sand of the arena of the Hippodrome de Paris, with a libretto by Victorin Jasset and a musical composition by Justin Clerice, stages the reconstruction of a Triumph as the Romans loved them with 850 extras, African princes, the beasts of the tamer Richard List, elephants, fighting dogs... Manuel Orazi creates sumptuous posters for what promises to be the ultimate "animated fresco" of its kind: the cinema will soon take over with spectacular means and resources that are far superior to these theatrical productions...

Nevertheless, until the 1920s, the Americans were not to be outdone and produced lavish extravaganzas where, once again, as with Solomon and The Queen of Sheba, their collections of exotic animals were widely used.

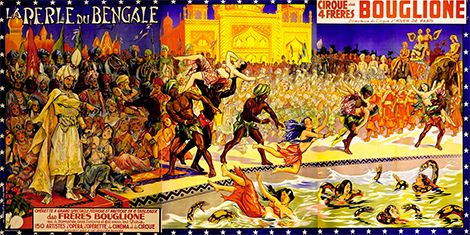

On the 13th of October 1933, the only performance of the pantomime Tarzan le maître de la Jungle, a pantomime whose sets and costumes have been rented from the German circus Busch, takes place at the Cirque d'Hiver directed by Gaston Desprez. For questions of unpaid fees and to avoid unfortunate lawsuits by Edgar Rice Burroughs' successors, Tarzan was quickly replaced by Les Fratellini en Afrique, a quickly written slapstick piece by the young director Géo Sandry, who was called to the rescue by Desprez. In 1934, the Bouglione brothers took over the management of the Cirque d'Hiver. With Géo Sandry, the providential man who staged most of these spectacular compositions, they developed a new genre, assimilated to circus operas or as an offbeat variation with a strong emphasis on the great theatrical operettas that have become a major attraction in some theatres.

La Perle du Bengale, created in 1935, presented for several months in Paris and on tour, shown several times until the 1950s, is undoubtedly the greatest success of the new direction of the Cirque d'Hiver.

In 2011, for the end of the year shows produced for the holidays, La Perle du Bengale returns to the stage as a long sequence of the program created by the Bouglione family presented in a large venue in Le Bourget. The original pantomime is "reincarnated" by a number whose sets, costumes and multiple animals on display are an evocation of the past splendours of the initial production.