Current figures

by Marcel Freydefont

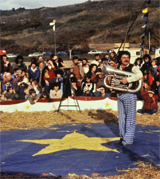

Taking an inventory of the big top and the travelling circus in this second decade of the 21st century in France, enables us to spot the figures that seem to characterise, beyond the most recent contemporary situation of the circus since the noughties, the situation of the performing arts in general, approached from the point of view of creation and diffusion in terms of a spatial strategy. Four shows illustrate this: Le Bal des Intouchables by the Colporteurs, Géométrie de caoutchouc by Compagnie 111, Secret by Cirque Ici, and Transversal Vagabond, cirque chic et pas cher by Philippe Goudard. These examples crystallise four ways of being and doing, involving infrastructure and logistical choices that are in keeping with the artistic aim. The titles of the shows provide eloquent clues.

This subject covers the multiple realities that intersect and need to be distinguished from each other. The terms at stake continually develop in an eminently complex geography and history, finally composing a sort of geometry of a rubber leaf. This expression defines the topology and study of spatial deformations. This science of continual transformations that stretch, unfurl, invert, twist and manipulate objects without breaking them, and "neither separate that which is united, nor stick together that which is separated," is suited to our subject, for there is something homothetic with the big top and with the circus. Talking about covering is appropriate, given that the big top is a portable shelter, a transportable structure that can be dismantled, and is composed, generally, of poles and a large canvas, anchored into the ground by pegs. The big top is a continual curved surface that envelops and generates spaces and sub-spaces, provoking a particular relation between the show and its abode, artists and audiences, inside and outside, interior and exterior, city and show. The terminological study is interesting as it specifies lexical roots and opens up to synonyms and analogies in a precious metaphoric and metonymic game.

Correspondences

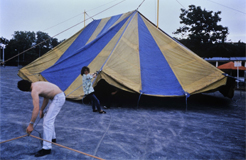

An examination of this type of structure enables us to distinguish between a big top with poles (umbrella or marabout tent with one pole, a big top with two, four, six etc. poles), a big top suspended from arches, a free-standing big top, a bamboo-big top, and an inflatable bubble, while considering the tent in a broader sense, i.e. as a textile structure, of which the big top has become one of the main figures. The cartographic study of places dedicated to the circus in France also reveals the confused realities between permanent and travelling circuses, a basic variation in the image of the human condition, between place and displacement.

In this way, the perfect correspondence is established between the big top, the circus and travelling, mainly from this all-important, circular performance space that is the ring or arena, multiplying occurrences, connotations signs, and appeals to an imaginary universe activated by engaged realities.

A popular art from, local entertainment, family outing, show for everyone, source of emotion, and variety act of physical disciplines, the circus reflects childhood, travel, dreams, and otherness. Such are the usual rather resilient clichés born of what is commonly called the traditional or classical circus, which in fact has modern origins (the circus is an 18th century invention, as opera is a 17th century invention).

In this respect, the current terminology does not lack ambiguity. Indeed how should the limits be drawn between these different names: ancient circus, classical circus, modern circus, traditional circus, old-fashioned circus, new circus, contemporary circus, creation circus, circus arts, and ring arts?

Like many other performing arts, including the theatre, dance, and opera, the circus is an equivocal form that overflows the apparent univocity of the genre, and exceeds the clichés that have forged its identity, without however, erasing these. To paraphrase Zola, the circus does not exist, there are several types, and everyone seeks their own. The unique aspect of the circus stems from the plurality of its expressions.

Variations

As we are talking of spatial strategy, we should also evoke the fluctuating spectre that governs both the circus and the theatre: fluctuations between shelter and edifice, or camp and barracks, to use Antoine Vitez's analysis, or, a permanent theatre or travelling circus. To these fluctuations we can add the decisive one between stage cube and circus sphere, between frontal stage and central ring. Firmin Gémier proclaimed that the permanent theatre was "a heresy" as the permanent theatre was "contrary to the vital principle" of theatre. This profession of faith established the theatre radically in the fluctuating game between the ephemeral and the permanent, appearance and disappearance, balance and imbalance, body and décor.

It is interesting to see the term big top and its and practice develop at the time that Gémier (who was, we know, attracted by the circus space) created the national travelling theatre at the very beginning of the 20th century. This strategic choice was supposed to respond to two aspirations: the "need for a nomadic life" which is at the very origin of the art of theatre (an allusion to Thespis' chariot and the Illustrious Theatre of Molière), and which is a need, Gémier specifies, "that our era, intellectually absorbed by the capital and the big cities, appears to have seriously misjudged." It was about conquering new audiences and an economically viable exploitation of the theatre that Catulle Mendes expressed in 1901, in a report on popular performances in the provinces, writing that there was not, "at a given site, a big enough fervent, or even curious crowd, to sustain a theatre year-round at one franc per ticket; but that there were enough people everywhere to house one brilliantly for a period of time1," which argued in favour of movement.

In 1911, taking advice from Barnum & Bailey's American engineers, Gémier created a 1,600 seat, fireproof canvas big top, for his theatre, which was to travel by railway. At the same time, between 1895 (the construction of an open-air covered stage that backed onto a mountain) and 1924 (construction of a closed, 1,000 seat room), Maurice Pottecher chose a permanent theatre for his Théâtre du Peuple in Bussang. These fluctuations continued to operate in the past and present. It is not about getting hung up on artificial oppositions, but about seizing the richness produced by these fluctuations. To take but one example, the use of a central stage (Cercles/Fictions, 2010, created at the Bouffes du Nord) by the Compagnie Louis Brouillard, experts in the black box and absolute darkness, demonstrated a sign of the times: a sort of syncretism through bringing together positions, which could appear to be disparate or opposing. It is important to measure the significance of the terms used, and to avoid any confusion.

![]() listen to the Prologue de la Liberté by Maurice Pottecher, spoken by Camille Pottecher in 1913

listen to the Prologue de la Liberté by Maurice Pottecher, spoken by Camille Pottecher in 1913

Terminological approach

Big top, tent, camp, caravan...

The French term chapiteau comes from the old French chapitel, from the latin capitellum, describing in architecture, "the part of the top of the column that rests on the shaft" (Littré). It is derived from capitulum, meaning little head, hat, hood, and a diminutive of the noun caput, meaning the head of a man or an animal, and, in the figurative sense, extremity, point, summit, main part, chief, and from the adjective capitalis, describing that which concerns the head. By extension, "one can talk of "cornices" and other crowns that are set above sideboards, wardrobes and other works; of the upper part of an alembic, in which the steam rising from the cucurbit condenses; a piece of cardboard in the shape of a funnel, placed at the top of a torch to catch any drops of wax; of a cornet placed at the top of a flying rocket, etc." (Dictionnaire de l'Académie Française, 8th edition, 1932 to 1935). Imagining the circus big top as the appropriate receptacle for the condensation of steam rising from the cucurbit is pretty creative: the emotional crescendo that fills it proves it. The radical – cap or – chap is a homonym for a false friend that is nevertheless interesting, stemming from the verb capere which means to take, contain, enclose, and which gives the terms capable, and capacity, whose meaning finds resonance with the notion of the big top. Hat and big top sit atop a head that is bubbling over with creativity, crowning it in some way. It is interesting to establish a link between the big top crown and that of the Charles Garnier's Opera stage.

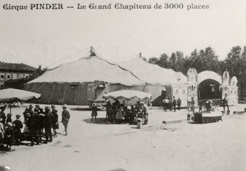

Emile Littré's Dictionnaire de la langue française published in 1973-1877 did not give the term chapiteau the meaning of a canvas structure destined for the circus. The 9th edition of the Dictionnaire de l’Académie Française (volume 1, published in 1992), belatedly provides the current circus definition: The circus big top, the tent in which the performance in held." This meaning has been used since 1919 to describe that canvas structure of the travelling circus, which is a sort of tent. This use was conveyed by the introduction of this accepted meaning in normal dictionaries. The Anglo-Saxon word big top reflects the idea of the summit.

The structure of the big top, either circular, elliptical, quadrangular, and with or without rounded extremities, is generally composed of poles, surrounding posts, a large specially designed canvas, and sometimes, intermediate poles called cornices. This structure is held in place by pegs (originally wooden pegs, then large steel stakes), which are inserted all around it, and propped up with ropes and straps. In some cases, a cupola tops the big top. This typical and changing structure is itself a historical variation on a form of vernacular and makeshift habitat: the tent, the principle of which dates back to the origins of humanity. A portable shelter composed of a cover (canvas, hide, leaves) and a standing structure, the tent differs from another type of makeshift habitat, the hut, in that the tent can be taken down, moved and put up again, whereas the hut is rebuilt at each step using materials found on the spot. Note that the Greek term for tent is σκηνή (skênê), which describes the actor's house, a canvas hut tangent to the orchestra, a circular space in the genesis of theatrical spaces in Greece.

Variations in use

As populations became more and more sedentary, a new use was found for the tent, in the form of military camps. The specific use of a certain type of tent by the circus was another example. Another use was tourism, with the development of camping, a word that appeared in 1903. Currently the tent has a well-documented humanitarian use.

A camp is a temporary installation in a given space. The circus camp is composed of one of more big tops, caravans and locomotion and traction vehicles. The caravan (originating in the 17th century) or verdine, is a car transformed into a dwelling, pulled most often by horses, related to the lifestyle of nomadic or fairground populations. The adventure of the Cirque Bidon showed, as early as 1974, the lasting appeal for the young generation of the day for this nomadic lifestyle: François Raulin's team still live in horse-drawn caravans. One of his last shows in 2013 was named Vite ralentir and was performed outdoors.

The place of the circus in cities can be defined as: part central and part marginal. The big top has often been set up in town squares, but had gradually been relegated to the outskirts of the city. In 1990, the Big Top at la Villette, one of the major spaces for contemporary circus shows in Paris, was an expression of the desire to reintegrate the urban fabric. Such spaces are included more and more in town planning programmes.

Travelling, wandering, on tour...

This notion is rich in meaning. The main sense of the French word itinérant (travelling) comes from the lower latin itinerans, the present participle of the verb itinerary, to travel, which comes from the substantive iter, meaning a path you take, a journey, or trip and is an antonym of sedentary, and fixed. The substantive first describes a person who moves around to exercise a responsibility, function, or profession. Itinerancy designates a movement according to an itinerary. An itinérant is not necessarily a nomad, but might be a sedentary person moving around. The itinerary in the old sense is a tale of travel. In a derived sense, the itinerary is the road you follow to get from A to B. In the figurative sense, the word designates inner, intellectual, moral, philosophical, and artistic progress. Iter comes form the verb ire meaning to go, and which led to itare in Latin, which means to do again, start again, with the substantive iteration, which means repetition, say again, do again. With its "one city, one day" approach, the circus is as iterative as it is itinerant.

Another French term used more often in the theatre is ambulant, from the Latin verb ambulare, meaning to walk, to come and go, and the substantive ambulation for walk. The French usually describe the circus as itinerant and the theatre as ambulant, where English uses the term "travelling." Since the Middle Ages, Europe has seen a number of travelling artists, often performing in outdoors spaces: medieval minstrels, troubadours, palquistes, barkers, acrobats, tumblers, jugglers, rope dancers, jumpers, bear tamers, and fire breathers, etc. They found their place in the circus, which brought them all together in their diversity while focussing on their differences.

Nomads

The notion of travelling is meant to be distinguished form that of roaming and vagabondage, which were long banned and regulated. Itinerancy has a point; roaming does not, nor does vagabondage, which describes the state of a person "with neither hearth nor home." This notion of itinerancy leads to an examination of nomadism. Nomadism is a way of populating and lace and a lifestyle based on moving from one place to another. Mankind was nomadic before it became sedentary. And some populations still practice this way of life today.

The 20th century generated a new type of nomadism, which was a semi-nomadism, or moderate nomadism, chosen rather than undergone for economic, tourist, social, cultural and artistic reasons. It seems necessary to distinguish this type of nomadism from historical nomadism (for example the Rom people) and the migratory phenomena of immigration and emigration that concern movement by people and group looking for new roots.

Travelling companies differ from companies on tour in that there is a supposition that the show and its dwelling moves. Thus, financial aid from the Ministry of Culture for the creation of travelling-circus arts is aimed at companies on tour with their big top.

Methods of transport

Obviously travelling is related to transport. The development of the big top was linked to that of methods of transport, first of all the railway, then cars, vans, and lorries. In this way, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, canvas big tops began to replace the constructions or semi-constructions that characterised circus architecture.

A canvas structure – initially named a canvas tent – was first used in the circus in 1825 in the United States, and was derived from military tents, a cone shaped tent with one pole, or a two-pole tent. Then came the circus tent, or big top, which was exported to England in 1838. That was the origin of the term "American tent." The American influence was also felt strongly in the crystallization of the modern circus and the landscape that it created in cities, with, mainly, the European big top tour of Barnum & Bailey's Greatest Show On Earth, in London in 1889 at Crystal Palace, then in 1897 and 1902 in the big top, except in Paris where it was set up in the Galerie des Machines on the Champ de Mars.

And in fact the term barnum came to be used as a noun. The use of the big top became more widespread after 1870, encouraged by the development of railways and cars, as well by technical progress: improvements in pole techniques, and lighter canvasses enabled higher and bigger tents. The invention of aerial disciplines such as the trapeze, requiring greater height, made use of these new possibilities. The new circus and the contemporary circus were notions forged in the 1980s and 1990s, and they emerged at the same time as the street arts were calling on the fairground arts, giving rise to new aesthetics that drew on the fringes of other art forms, mostly the visual arts, dance, theatre, music and opera.

This transformation was also due to an economic change driven by a crisis in the traditional circus, which was trapped in the televisual image stemming from La Piste aux Etoiles from 1956 to 1978. In 1978, the governing ministry for the French circus changed Agriculture to Culture, meaning that the circus would now benefit from a modernisation fund and public aid. In 1983, Jack Lang confirmed and specified the elements of a public policy in favour of the circus arts, open to encouraging creation and innovation.

One of the consequences was the real aesthetic transformation and the relative transformation from a structural and construction point of view, of the big top. For Archaos, "the development of the circus must happen through a transformation of the womb that has carried it for 200 years: the big top and its ring… Every Archaos show has suggested a specific, scenographic exterior, specially designed for every show." The Chapiteau de corde (1987), with its spider's web demonstrated that Archaos would do away with the sacrosanct circus ring. The Volière Dromesko (1990) is "more than a big top; it is the box that forms the décor of the show." The same goes for Hans-Walter Müller's bubble design for Kayassine (1998). Or that of the Théâtre du Centaure's big top by architect Patrick Bouchain for an adaptation of Macbeth (2001). Finally, let us mention the Compagnie Off's open metal cylinder for Carmen-Opéra de rue (1999), and a destructured big top for Pagliacci ! (2011). This search for a scenographic unit that is part exterior, part ring and apparatus, and part show, is a shared reality.

1. Quoted by Nathalie Coutelet in Démocratisation du spectacle et idéal républicain, L’Harmattan, Paris, 2012, p. 183.