A new architecture

by Christian Dupavillon

Just like the Franconis, new circus families were flourishing. The Plèges, Roches, Pourtiers, Ducos, Palisses, Rancys, Medranos, all travelled by means of wooden buildings, "circus-constructions”, structures built for the duration of the performances and tidied away for the rest of the year, and "Circus semi-constructions", temporary buildings that they carried parts of with them.

Family circuses

Wood and roofing felt or tarpaulin for the roof were the only materials that they were built from. The architecture was the same: a polygonal structure consisting of fixed and demountable half roof-trusses that rested on posts and covered: the 13.5 metre diameter ring, an entrance for artists with its curtain hiding them from view, its platform for the musicians, the rows of seating surrounding the ring and the stables. The diameter of the building would range from 24 to 40 metres depending on the number of spectators. The architect was the head of the family. Theodore Rancy designed more than two hundred circus-constructions. When it came to a semi-construction, the circus would carry the roof frame’s half trusses, the seating racks, the entrance, the facade, the seats and benches with it. The boards used for the surrounding walls, the steps and the benches were bought at each location and sold at auction at the end of the last performance. The circus usually had two semi-constructions, the first being used for performances in one city, while the second was being transported and built in the following city. To make such an organisation profitable, each stage lasted at least three weeks. Outside Paris and the big cities, the circus was the only local attraction until the end of the 19th century. Its arrival, construction and parade, fascinated the public.

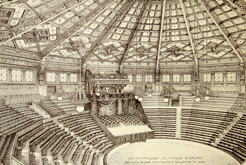

The difficulty of building a circus, be it a circus-construction or a permanent circus, was covering its pavilion, the vast central space. In those days, large reaches were made possible using iron. The Crystal Palace in London in 1851, the Galerie des Machines in Paris in 1889, the various versions of the Hippodrome de Paris, testify to the development of daring metal frames. They would be popularised by the German constructions and semi-constructions in the 1930s.

The first permanent circus buildings outside of Paris, lesser versions of the wooden constructions built in stone and rubble, were family-owned. Their architects were the heads of the family, skilful builders who, most of the time, could not read or write. Franconi built a permanent circus in Rouen, Théodore Rancy in Boulogne-sur-Mer in 1866, in Geneva in 1880, and two years later in Lyon.

In Germany, the big circus families built real palaces. They divided up the Prussian territory and its neighbouring countries by taking up residence in cities where they established themselves and pitched themselves against each other, not only in the ring but also through the means of the architecture they offered. The Schumann’s triumphed in Frankfurt and Vienna, the Busch’s in Berlin, Hamburg, Breslau and Vienna, the Renz’s in Berlin, Hamburg, Breslau, Frankfurt, Vienna and Copenhagen, Sarrasani in Dresden, the Hagenbeck’s in Essen and Stuttgart, the Krone’s in Munich, Les Carré’s in Cologne and Amsterdam, which did not prevent them from traveling by means of their semi-constructions and big tops. The stuff that the spectator’s dreams are made of: the entrance of their canvas cities often had the appearance of the palace from the Thousand and One Nights. The permanent circuses, monuments to their glory, competed in size and outward appearance. Often their architects counterfeited the buildings that were in vogue. For his circus in Dresden, the largest in Europe, Sarrasani copied the famous concrete dome of the Landesbibliothek built by the architect Max Berg a few hundred meters away. None of these circuses in Germany and Austria would survive the destruction of the war.

Apart from the permanent circuses built in the USSR, most of these buildings date from the second half of the 19th century. The Cirque d'Hiver was built in 1852 under the Second Republic of France and was inaugurated by Napoleon III during his first public appearance. The circus of Reims was built in 1867 under the Second Empire, that of Amiens in 1889, of Elbeuf in 1892, and of Troyes in 1905 under the Third Republic. Only the sign engraved on the entablature changed. The circus became imperial, royal, national, local.

City circuses

In France, when they were not family-owned, the permanent circuses were public establishments, built where the Rancy’s, Plège’s and others set down their constructions. The municipalities were forced to replace the fragile and unsanitary wooden installations with permanent ones. From 1800 to 1851, there were only 70 theatre projects in France compared to 938 church projects, 450 prisons and asylums and 354 administrative buildings and town halls. Rouen, Valenciennes, Dijon, Angers and Bordeaux equipped themselves with permanent circuses, that hosted, other than the touring troupes that sojourned there, concerts, plays, meetings and film screenings. In 1888, the Boulogne-sur-Mer Circus even became the Omnia Cinéma Pathé.

In Troyes, the public circus, inaugurated in 1905, took over the place of a circus construction. In Boulogne-sur-Mer, on the banks of the Liane, a Rancy building was reconverted into a stable. The new Municipal Circus of Amiens, built by Napoléon Rancy, was erected on the site of an old construction, Place de Longueville. "Instead of the enormous cryptogam, which was gathering dust in its corner, stood (...) a sort of gigantic and splendid narghile in the centre of a panorama of greenery; its chiselled pipe, finished with a metal book, even let out a light smoke, and its incense-burner, all aglow, sparkled under the Amiens sky.” wrote Jules Verne in his inaugural address in 1889.

The architecture of the permanent municipal circus was as much inspired by that of the circus constructions and semi-constructions as by the official art of public buildings. The style was neoclassical. "The eight fluted tent columns of composite material, remarkably delicate in their execution" of the pediment porch of the Circus of Amiens were inspired, according to Jules Verne, by those of the Cirque d’Eté that Hittorff had drawn half a century earlier. Its architect did not go as far as to colour them in, like those which inspired them were.

The interior was inspired by the circus constructions. They boasted the same starkness and rudimentary layout, with no entrance hall, no grand staircase or foyer; just a ring, at times supplemented with a forward-facing stage which served to make the space more versatile, as seen to a certain extent in Amiens and above all in Elbeuf, like in an Italian-style theatre. It fell upon the city’s architect to construct the building in the same style as the other local buildings. The project manager of the Amiens Circus was the regional chief architect; creator of the Museum of Picardy, the Posts and Telegraphs Hotel, the mental asylum, schools, churches and convents…

State Circuses

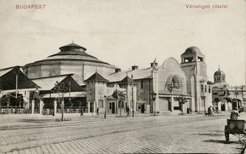

The only examples of state circuses are those built by the Soviet Union. The tradition of permanent circuses existed in St. Petersburg with the Circus Ciniselli built in 1868, in Warsaw with the Linoleum, in Budapest with the winter circus Fövarosi Nagycirkusz in 1878, and in Moscow with the Old Circus in 1880.

The Soviet Union used the circus to serve its ideology. According to them, unlike the other arts, the circus did not present a political risk. Its image was that of a professional and popular entertainment that the regime developed as much across the country as in its allied republics. Around fifty of these permanent state circuses were built between 1950 and 1970. Their standards were imposed by on high. Less solemn than in Moscow and St. Petersburg, the dimensions of these buildings were nevertheless imposing, the facades were made from glass, the domed roof from reinforced concrete which, when bare, resembled marble. The largest amphitheatre had 3,500 seats and each spectator was equally placed. This is the style of the national architecture, known as "socialist", which took over from the Stalinist architecture which Krushchev denounced as extravagant in 1956.

Moscow built a new, 3,000-seat circus in 1971: the Bolshoi (or Grand) Circus. The Sochi Circus, on the Black Sea, was also constructed in 1971. They were followed by Omsk, in western Siberia; Frunze , Kirghizstan; Alma-Alta, Kazakhstan; Yekaterinburg, Sverdlovsk Oblast; Gorki, with the Nikitine Circus; Kazan, in 1967, Tashkent and more.

At the time, in the name of friendship, the USSR also provided the capitals of the socialist republics with state circuses. Some of those permanent circuses are now in ruins. All that’s left of the State Circus in Grozny, Chechnya, which was inaugurated in 1976, is a pile of scrap metal. The one in Ulan-Bator, Mongolia, built in 1924, was abandoned in 1992, when Mongolia became an independent nation. Construction of the National Circus on Avenue Mao in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, ground to a halt when the Russians left the country, in 1989. The structure’s framework, which had been made in Russia, mouldered for years before it was turned into a nightclub.

In France, stable circuses have been rehabilitated in recent years, however, most notably in Amiens, the centre of the Pôle National des Arts du cirque et de la Rue/National Circus and Street Arts Pole; and Elbeuf, while others have been transformed. The one in Troyes was turned into the Théâtre de Champagne in 1978; the one in Douai was converted into a cultural centre in 1980; and the municipal circus of Châlons-sur-Marne, which has since been rechristened Châlons-en-Champagne, has housed the CNAC since 1985. These transformations surely saved the structures from their likely demise. Renovated stable circuses – or even future ones, after all – have a role to play both in sanctioning the circus renewal and in helping urban centres to thrive.