Codification of roaming and mobility

by Pascal Jacob

By developing a canvas architecture and making it into an easily dismountable and transportable theatre, the American Joshua Purdy Brown created the principle of travelling and applied it to an artistic form which was more accustomed to the comfort of walls and timber frameworks than the unavoidable currents of air in such a structure.

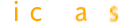

While shaping his "umbrella", Brown took on the fragility of a tent, but demanded above all that it be simple to install, with compact equipment; essential for traveling at low cost. A few bundles of canvas, wooden stakes and a tent-pole were enough to build what would become a real symbol of the travelling circus: the big top. The comfort was rudimentary: a few chairs for "distinguished guests" would be borrowed from the nearest inn and placed at the edge of the ring while the rest of the audience would stand behind, admiring the aerial drills and acrobatic feats of troupes mostly made up of a few horsemen, a clown and a handful of acrobats by the light of resinous and crackling wooden torches.

Several reasons prevail over the implementation of this structural innovation: the weak regional urban network which could not sustain settling for long periods of time in cities that were far too small to be profitable in the long term and which justified the choice of frivolity; the difficulty of renewing the star attractions that made up the play bill in a country that had discovered equestrian games less than thirty years ago; and the fact that the big top was very easy to set up. Not to mention extremely ductile.

In 1888 in the United States, the arrival of three juxtaposing rings made it possible to create a linear layout where it sufficed to add tent-poles and stretch the tent, thereby creating gigantic canvas naves where thousands of spectators could take their places. In 1926, Hans Stosch Sarrasani, newly returned from a triumphant tour of South America, invested his profits in the modernisation of his equipment and modelled his big top on the so-called German style by placing the ring between four tent-poles, crowned by a circular dome.

The case study would not be complete without evoking the architecture of the permanent circuses. Even if they were not able to widen the surface of their tents indefinitely, it was possible to accommodate several thousand spectators on circular rows of seats; a way of creating a paradoxical intimacy which would be unimaginable in an American-style big top where the seating sometimes extend over several hundred meters...

The circus in the city

The big top disrupts all the established codes: the troupes go from construction to destruction, from anchorage to instability, from a lasting bond to a fleeting incident.

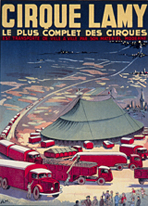

Permanent circuses are comparable to urban monuments, architectural landmarks akin to the public buildings that structure a city, from theatres to stations or museums. The troupe that resides there does not change its integrity. The horses are settled in the stables and the artists unpack their belongings in the dressing rooms. The building assimilates its new components, but let’s nothing show on the outside except, from time to time, a banner of flamboyant colours hung on the facade to announce the performances. The big top, on the contrary, is a predator. It seizes an empty space, settles there and drastically disturbs its layout. The local people who are used to crossing the square or the fairground can no longer do so. In the space of one night, the earth is upturned, long metal poles are planted in the ground and instead of a playground or a space for walking, another city is erected... Multicoloured vans, strange smells and unidentified noises will give rhythm to the lives of the surprised, resigned or furious citizens for a few hours. The set-up is an intrusion to all. It is a fortress that seems to taunt the surrounding houses, its flags flapping in the wind and its insurmountable walls which are intended to hide the men and animals until the fateful hour of resolution, of sharing and meeting between two communities, the moment when the doors open half-way, where ordinary mortals are invited to enter the mysterious lair that will soon disappear.

Praise of mobility

The system of travelling from one building to another offers some comfort, but it is also sometimes double-edged sword. For example, in the case of a northern city bereaved by tragedy such as a recent mining accident, no inhabitant will have the heart to go to the circus. If the troupe has rented the circus for several weeks, this is a financial catastrophe and the sign of probable bankruptcy, if only because the next rental will only be available after this first stage is over, in a month’s time or more... With a big top, the symbol of independence and freedom, one just needs to change the itinerary, losing a day or two to get as far away as possible from the epicentre of the tragedy and resuming the tour some tens or hundreds of kilometres away, in another region and in other cities.

From this point on, and this is a dimension that will be further simplified by the motorisation of transport vehicles, the circus discovers mobility and self-sufficiency. To save time, it travels with everything it needs and crosses distances with avidity. It travels by night, unfolds at dawn, performs at dusk and disappears again into the darkness without leaving a trace... It is the big top that induced this rapidity of movement and made the circus of the twentieth century a model of speed and efficiency summed up by the expression of the trade: "making a day’s city". Until this point, it was a question of transporting a show from one city to another, but from now on it would be a canvas city that moves, with arms and baggage, like a small well-trained army, experienced in all the complexities of the drill. It is certainly no coincidence that the Japanese high command regularly sent officers to assemble and dismantle the Hagenbeck circus during its tour in the islands of the Rising Sun in 1933...

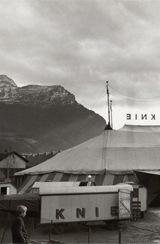

- Denmark’s Circus Arena building-up and pulling down the Big Top