by Pascal Jacob

The taste for the untamed, for the wild beast and the fierce, gradually replaced by the taste for risk and blood, is the source of an eternal curiosity for the wild world. Many civilizations have chosen animals for protective powers, from the crocodile to the jaguar or the bear to the snake, these symbolic associations are the part of the sacred that binds man to animal for millennia. The presence within the community itself of one or more representatives of the species revered, the antithesis of any domestication, suggests a first level of insertion of the wild into the unexpected scope of the city.

From the jungle to the ring

In Thebes, the crocodile is venerated, and its worshippers tame it by offering it delicacies while adorning it with bracelets and necklaces of gold and precious stones. Carefully tended to in its lifetime, at its death it is embalmed and placed in a sacred burial according to the same rites and rituals as those observed for humans. Whether it is a source of devotion or a pretext for amazement, the wild animal poses new challenges as it questions the imagination of all peoples and it gradually becomes sought after.

The search for a distant land elsewhere, synonymous with discoveries and wealth, haunts the West since the Greek and Roman conquests. Modern colonization took off with the advent of explorations, initiated by Portugal and Spain. Portuguese sailors began to systematically visit the African coasts from 1418 onwards, extending to the Indian Ocean in 1788. The Genoese Christopher Columbus landed on the island of San Salvador in 1492 before reaching the Cuban coast, convinced that he had discovered India.

In 1798 the Portuguese Vasco de Gama reached India, the real India, and opened a trade route to Asia. His compatriot Pedro Alvares Cabral takes possession of Brazil on behalf of the Portuguese crown in 1500. These ardent discoverers (descubridores) drastically alter the balance of the world: by making countless wonders accessible, they open a new Pandora's box and awaken desire, interest, covetousness and greed. Solicited and convinced, several European courts appoint and mandate shipowners and explorers to conquer ever more lands and wealth, including among them, of course, live animals.

France, the United Provinces of the Netherlands and England create and develop their colonial empires in the 17th century, while at the same time the Danish and Swedish crowns extend their possessions. Dutch shipowners are the first to trade with live animals: they are thus unrelentingly fuelling the emergence of a universal curiosity.

Curiosities

Civilisation is full of dissatisfaction: animated by an acute awareness of its development, it constantly provides its actors with reasons to change their perception of the world. The travelling performers and the circus artists have perfectly grasped this nuance by adding impatience to their performances, modelling chance and destiny, constantly creating new ways of interpreting the living.

The development of trade routes promotes the accessibility and perception of thousands of unknown or unrecognized animal species and contributes to defining the reality of the world. The first cabinets of curiosities, these Wunderkammer cabinets filled with precious objects, naturalized or living creatures, like the one from Rodolphe II immortalized by sumptuous richly illustrated catalogues, are both the ancestors of museums and by extension also menageries. These collections are multiplied by princely or royal commissions of vellum paintings which fix and facilitate the understanding of countless floral or faunal representations. Very quickly, the taste for exoticism spreads in civil society and fairground entrepreneurs take over this new mode of expression: developing an epic narrative based on exhibited animals. The procurement of exotic animals remains uncertain, but a market is gradually being organised.

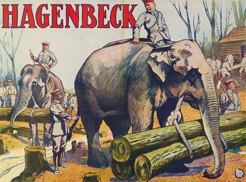

To meet the ever-increasing demand for rare and strange animals, well-stocked merchants are needed. Motivated by the benefits of this providential and seemingly inexhaustible windfall, some savvy traders will implement a system of catching and transporting wild animals that will enable them to satisfy increasingly precise orders, but also to be able to offer their customers unknown and, inevitably, desirable animals. The Germans, the Reiche and the Hagenbeck, will open the great ball of animal kingdom marketing and put on the market thousands of living creatures available on simple shopping lists, with their characteristics and prices. Boas and pythons can be bought by the metre and the beasts and wild animals are offered in groups already tamed, with caged carriage and presentation stools. It is a new vision of the world, a reassessment of the principles of rarity and inaccessibility: from now on almost any animal, from the scorpion to the elephant, but also from the anoa to the cassowary, can be purchased in Hamburg and shipped a few days later to the delivery address indicated on the order form.

This extraordinary accessibility will initially promote the development of menageries, but it will very quickly transform the exotic animal into a new symbol for the circus.

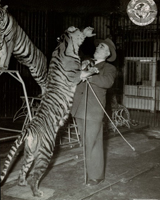

Men and beasts

Entering the premises of a menagerie is an attempt to spot the brutality of the world, even if it is sometimes draped in red velvet and masked by a few palm trees in pots, encapsulated in the wooden and steel panels of a small makeshift stage, the cage-theatre.

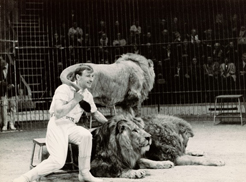

The reality in this particular case is an intuition of possible death, an unexpected scarification in a daily life without surprises and which will never leave the spectators' imagination. The menagerie rekindles an almost faded link, a missing link between the close combination of the fierce ages and the sudden proximity of the cages. To nurture a brand-new fascination, bodies must abandon themselves, animals must feign and roar, some blood must flow, a bitter mixture of dust, sweat and hot straw must strike the public's subconscious forever. Terror and hope are needed, but above all, the truth is what makes the exhibition successful. The confrontation with wild animals is not based on anything else. An unprecedented brilliance that will eliminate the certainties of those who watch, get scared and admire those who take all the risks, absorb the fears of an entire community and are honoured at the end of an ever-uncertain commitment. There is a cathartic dimension to these regular confrontations in front of a fascinated community.

The animal tamer appears to seek to embody progress, the victory of human intelligence over the accepted animal's brutality, reduced to using his claws and fangs to fight against demands that are sometimes far beyond his everyday life in the wild. The sustained ferocity of the lions, tigers or panthers is very much in keeping with this reduction of both world and time: this display of senseless courage and raging violence is a powerful plot capable of convincing audiences and chroniclers for several decades in Europe and America.

From the early 19th century, lions, tigers, leopards, pumas, jaguars, sumptuous fragments of savannah or jungle, tattooed from one century to the next by the glowing torches or bright spotlights, are the main features of mobile menageries. They attract the customers and fill the stands: initially, their exhibition behind solid bars is enough to keep the crowds coming, but interest fades gradually, and the founders of these establishments begin to explore new ways of attracting visitors. A handful of men and women will take up what looks more like a challenge than a vocation, but their desire to control the savagery of their residents will transform them into the heirs of the Roman handlers.

Overcoming Fear

The fascination for danger is ancestral. When it comes to understanding the motivations of someone who chooses to enter into a central cage to confront wild animals, there is little literature on the subject. The practitioners' notes and reports are often edifying: from Henri Martin (1793-1882) to Upilio Faimali (1826-1894), from François Bidel (1839-1909) to Alfred Court (1883-1977) or from Roger Spessardy to Mike Baray (1938-) not to mention Carl Hagenbeck and Firmin Bouglione, they weave a strange and audacious garland of memories over the pages where animals do not always have the best role, but they also feed the fantasies of generations of readers. It may not be the most reliable source of historical truth, but these adventures can seem epic sometimes. Alone in the cage, the animal tamer embraces his role as a hero and pushes the limits of obscurantism into the depths of darkness. At a time when the Beast of Gévaudan terrorizes the countryside, there is no other reason for the vogue of trained wolves: it is about exorcising a collective fear by controlling wild animals that are considered to be merciless. This is a troubling mixture of domination and conjuration. The success of the tamers at the Belle Époque does not draw on any other sources, except that it is also tinged with romantic nostalgia. Henri Martin or Isaac Van Amburgh apply empirical approaches and methodologies, but they are part of an intuitive lineage that goes back to the handlers, officers of the imperial house attached to the amphitheatre and likely ancestors of our modern trainers. With one of them in the Netherlands and the other in America, these two men model a new layer of ambivalent relations between man and animal, but above all, they revitalize fragments of a forgotten memory. In Rome, the public amuses themselves with songbirds, with eagles able to carry a rabbit between their claws without hurting it, or they marvel at the extraordinary spectacle of tightrope elephants patiently trained to walk on two ropes stretched over the sand.

In the ring!

The notion of work, regularly associated with that of dressage, reveals a strange contradiction with the principle of freedom inherent in the wild world. On the basis of this equation, it is as if the beasts had to work hard to pay a symbolic debt contracted in the Judeo-Christian mysticism during the expulsion from earthly Paradise. There lies a possible explanation for the presence in the cage of a lamb among the wild animals or, where permitted by law, the presence of a child, protected by a man capable of dominating the beasts. The tamer, dressed in a gown with biblical accents, controls his raging pack and embodies with a mixture of magnetism and authority a Deus ex Machina on a background of painted woodwork or red velvet.

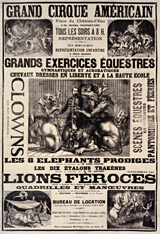

The intrusion of the wild in an elegant and romantic context, suddenly struck by imagination, caught up in the harshest reality, will soon represent a crucial stage in the evolution of the circus. The American Myers is the person who best synthesizes the fusion of the genres: without renouncing the equestrian games, he integrates in his programs some wild animals presented in a caged carriage installed in the middle of the ring, scenographic and technical transition between the cage-theatre and the central stage. Myers also owns a group of trained elephants. This is a real departure from a presentation mode that favours a star individual rather than a herd of animals which, as a result, are inevitably rendered anonymous. Myers is a pioneer, but he also announces dark days for the circus of his forefathers, replaced by ever larger caravanserai, always more conquering and especially more popular.

With a style long considered as initiatory and reserved for a certain fringe of society, the circus begins an inexorable mutation which will make it become a mass leisure activity where trained lions, tigers, elephants and chimpanzees replace horses, playing the wild card at the expense of the reassuring one. The fascination is intact, but the codes of representation are pulverized. Symbolically associated with an itinerant Noah's Ark, the circus enters a new phase of its history.