by Pascal Jacob

Animal education, based on impregnation and learning, is divided into two main streams that will shape two distinct environments: breeding and training. Correspondingly, taming and learning help to consolidate a range of techniques where constraints and rewards go hand in hand to achieve jumps, balances and anthropomorphic attitudes.

Savants and subjects

The Théâtre of the Italian Jacques Corvi, founded around 1840, brings together monkeys and dogs to juxtapose sketches inspired by various facts or sequences from everyday life. The Russian trainer Vladimir Dourov in 1907 did exactly the same thing when he created an attraction of a particular kind intended to fill the second part of a programme. A miniature train, a station, a railway switch and a whole small group of animals gathered on the track to illustrate an ironic and offbeat fresco.

Endowed with exceptional faculties of understanding, the different breeds of dogs apply themselves in particular to playing a multitude of roles established in relation to their size, power, agility or ferocity. The diversity of breeds offers an unusual range of possibilities for trainers who choose to show dogs.

In response to Arthur von Lipinski's 40 dog actors of all breeds, we find the Pekingese of David Rosaire, the Dalmatians of Madame Lorent, the dachshunds of Diana Vedyashkina, the poodles of Evelyn Hans, of Viviana, of the Chabre or Gérard Soules, the football playing boxers of the Dubskys or Lola, the phlegmatic and virtuoso backwards walking basset of Douglas Kossmayer alias Eddie Windsor, but also the barzoids of Marie Molliens or the canine partners of the Cirque Aïtal.

All the animal trainers in the world are looking for a "subject", an animal with exceptional abilities that will be able to assimilate a greater number of commands than average for its counterparts and behave in public in an almost "supernatural" manner. The novel Les Baltringues by Ludovic Roubaudi evokes this very particular theme with an extraordinary dog at the heart of the plot. Between 1814 and 1820, Munito, a calculating dog introduced by a Dutchman named Nief, was admired by spectators and chroniclers alike. Nicknamed the "Newton of the canine race", Munito is a white poodle groomed in the English style, that is, similar to a miniature lion. It is, of course, a "subject".

As they get closer to humans, some exceptional animals unexpectedly mark out the question of anthropomorphism and suggest another level of learning reserved for an informal and random "elite". Above all, they make it possible to identify another group of singular animals, integrated into the intuitive framework of many civilisations.

Representations

Animal, from the Latin animalis, is a word formed from anima, a term that identifies a vital principle, a breath, a soul. It gradually evolves to identify an organism, endowed with life and certain faculties. Appreciated, distinguished, but not always equal, animals evolve in human societies according to the expectations of those who own them, but also according to what they embody from one civilisation to the next.

Linked to the cult of many deities, some animals divide the animal kingdom and stratify it, but above all their supposed intelligence gives them access to a system of representations that definitively dissociates them from a multitude of less valued species.

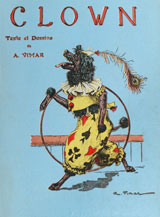

Painted, sculpted, woven, embroidered, the animals of the "first circle" invade walls, facades, draperies, tapestries, fabrics of all kinds, but also settle magnificently in the heart of many homes. There, from humble miniatures made of clay or wood for children's use to sumptuous pieces of ivory, bronze, gold or silver for credences or middle tables, the animal becomes king. There is sometimes very little from the representation to the incarnation and by the grace of skilful authors, the animals become more learned than men over the pages. There is no doubt that itinerant trainers, active since antiquity, have played a role, between emulation and inspiration, in defining a first structure of characters and attitudes.

Literary animals

Aesop, a Greek writer who lived in the 6th century BCE, composed several hundred fables in which animals played many roles. Gathered in a collection compiled after his death, these fables will be a formidable source of inspiration for many authors, from Phaedrus, a 1st century Latin fabulist, to Jalâl ad-Din Rûmî, a 13th century Persian mystic, to Jean de La Fontaine whose work has largely contributed to the insertion of animals in the collective imagination by dressing them with familiar and often very human behaviour traits. From the physiognomonic analogies of Charles Le Brun to the zoomorphic universe created by Granville, from La Petite Renarde Rusée by Leoš Janáček to Chantecler by Edmond Rostand or Walt Disney by Georges Orwell, animals interact with the symbols of a humanity both powerful and fragile.

Esmeralda, the brilliant saltimbanque who enchants Victor Hugo's pages of Notre Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre-Dame), has Djali as her partner, a white goat with golden horns, a creature of strong character whose heirs have made it a specialty to climb up mountains of chairs in the rings of countless small circuses whose gantries or tents can be seen erected under the sky on bright early summer's days. An animal with an agile foot, a stoic creature, the goat is content with little and proves to be a good recruit to spice up a performance under the stars.

Hector Malot's novel Sans Famille is a milestone in the transformation of kind creatures into rational, savant animals. The dog Capi and the monkey Jolicoeur participate in this idyllic and fantasised vision of animals made more human than their masters by the grace of their willingness to learn to behave well in society. Adorned with sparkling attire, crowned by the author with an extraordinary intelligence, these two animals, now savant, anchor their fellow creatures in a touching and ridiculous parody of humanity, but they also mark the time of gratitude for animals often considered as kind servants. In another register, Jack London's Michaël chien de cirque, published in New York in 1917, reveals with unexpected acuity the main characteristics and weaknesses of a unique system. Beyond the vindictive spirit that will help shape the rejection of Western societies in all aspects of dressage techniques, Jack London bluntly denounces methods of another age and condemns in essence the simple idea of submission that could inadvertently enchain two representatives of the same kingdom. In England in 1957, the book led to the founding of a Society for the Protection of Captive Animals, which opposed training in all its forms and advocated for the outright abolition of travelling menageries and circuses. Since the 1970s, the Society has been lobbying the European institutions to promote the harmonisation of legislation in the Member States of the Union. Jack London's novel crystallises an awareness on a global scale and inspires us to have a different view of our animals.

Instead of a proven fascination with animals capable of substituting themselves for men to better please them, we now prefer to evoke a form of conscious respect, which does not exclude a sense of admiration in any way.