by Marika Maymard

How can domestic animals, raised to carry loads, guard the house, be eaten or caressed, become "savant"? Domesticated for utilitarian purposes, animals are an integral part of the home [domus in Latin] ruled, governed by the head of the family [dominus]. Over the millennia, the selection, taming and breeding practices have altered and genetically modified the wild animals that have been subjected to them. The closest examples of animals that have lived with humans for a very long time are probably cattle [bos taurus], pigs, horses and dogs. Members of a horde or a herd with a highly codified organisation in the wild, they now find themselves caught as isolated animals in a unique relationship with their master, their instructor and, it must be said clearly, their trainer. First in the inn courtyards and lounges, in the huts and fairgrounds, then in the circus rings, dogs, cats, donkeys, mules but also pigs, geese, hens and rabbits, are chosen and in a way, inducted as intelligent and skilful "savant animals".

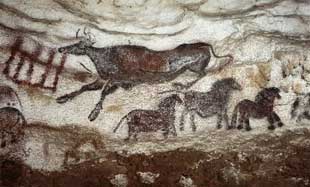

It is said, a little quickly, of the horse, but certainly more so of the dog that they are "man's best friends". Does this mean that they chose a long time ago to join and serve him? Supposedly descended from the wolf, the dog, under examination, would only share its genetic heritage with the grey wolf – Canis lupus – domesticated about 15,000 years ago, during the era of the nomadic hunter-gatherers. Complementary in the exercise of specific know-how, they came together as allies and partners, sharing the same prey, especially herbivores, and organising a common hunt, as explained by J. Paul Mégard in "La domestication animale n’est plus tout-à-fait une énigme" ("Animal domestication is no longer entirely an enigma"). [In La Lettre de la SECAS, No. 89, 2017].

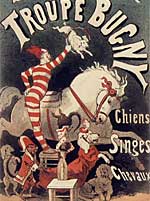

The wolf, which has remained wild, even trained, is exhibited, like other wild animals, in fairgrounds and in the rings. The tamed, "educated" dog shares the success and status of a skilful animal with the monkey and other everyday companions who are renowned for their grace, agility or, on the contrary, their clumsy and funny temperament, and certain listening and understanding skills are exploitable for a performance.

Partners

In the 19th century, the dog or the pig were as essential to the mime and acrobat clown as his violin or his frock. Accomplices, similarly, dressed in collars and small hats, they barge into the ring on a polka played by the orchestra while allowing the pickers to take away with them backstage the props and devices that clutter the ring. Almost mute, they express themselves in movement, competing with acrobatic prowess or comic leaps and bounds.

Originally from Yorkshire, the clown Boswell developed with his Newfoundland dog a burlesque duo dedicated to a chronicle by Théophile Gautier in 1851. He went to court for punishing a wine merchant who had kicked Yon, his little partner, in the vicinity of the Cirque d'Hiver. In the 1930s, the dog of the Fratellini trio dressed as a fox pursued the deer in the pantomime of the Cirque d'Hiver La chasse à courre. The little dogs of the Russian clowns Karandach or, more recently, Boiarinov, as well as Knuckleburry, the inseparable partner of the American clown Lou Jacobs, slip into a small suit and play the roles of elephant or rabbit. The menagerie wagons of fanciful trainers are a combination of species. The dogs are paired with the donkeys of Old Regnas a touching old man, a cousin of the emblematic Lord Sanger, named after him with his name backwards. Krenzola mischievously exposes his little poodle to the appetites of a dog, a fox and his golden eagle.

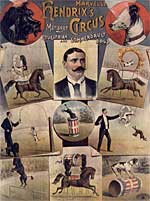

Stronger and stronger

The programmes at the end of the 19th century announced performances performed only by dogs, Miss Dora's little family, Cécilia Haaÿ's "monome des toutous" or Wallenda's dogs. In the 20th century, we can see Maurice Cherrey's seven Samoyeds with their immaculate coat, with the most skilful of them playing Au clair de la lune at the piano, the fifteen little Tenerife acrobats from the Ybis, the Strassburger or Rosaire squire dogs, Teddy Lorent's mini Dalmatian cavalry or Eric Braun's mischievous group. Descendants of the well-known barbets of the Pont Neuf onlookers in the 18th century, the dancing poodles of the Chabre, the royal poodles of Miss Moune with their rope skipping, or the fur balls that escape in a joyful brouhaha from the crinolines of Evelyne Hans or Viviana do not fail to attract visitors. Standing on their hind legs, diligent, stretched in their effort, they turn on themselves and cross over cavalettis and tiny hoops. Surfing on the whims of the times, the Dubskys, of Danish origin, borrowed from an Italian, Mr. Boëtti, the idea of training football dogs that he introduced in the 1910s. For thirty years, the Dubskys' boxers’ teams, striving to score goals with strong "headers" in the opposing camp, eclipsed the initiatives of Kita Sobolewski in the 1950s or Franco Knie in the 1980s. Their name remains firmly associated with the attraction.

Educated animals

"Happy," says Juvenal, "are the peoples who see their deities born in the gardens, in the farmyards, in the kennels," reports Elzéar Blaze in his Histoire du Chien in 1842.

There are many stories about the exploits of dogs with remarkable observation skills and reaction capacity. Known as intelligent, they show at least very high levels of attention to what their master expects from them and the discreet signs he sends them. The Enlightenment has given birth to generations of scientists, street and fair teachers, tooth pullers, sellers of elixirs and multiple experiments. The 19th century, which honours the sacrosanct Progress, was particularly favourable to the exhibition, considered scientific, of skilful animals. The most famous, on either side of the Channel, is the dog Munito, who entertained salons and theatres from 1814 to 1820. Focused, the calculating barbet refers to playing cards, chess or domino pieces and all the numbers and letters that allow him to win every time and to read and write words.

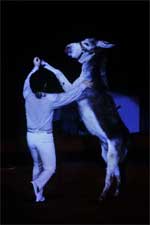

Lessons were also learned at the stable: to diversify the exercises of an academic equestrian circus, riders, giving in to the fashion of anthropomorphic animals, invented comic roles for horses, starting with Astley and his brigand Dick Turpin. Some trainers exploit the ability of some donkeys to follow the music and develop singing or dancing donkeys.

In the panel of skilful animals, the cat, expressing little interest, except for treats, is approached with caution. A form of gentle training that suits this little feline is based on a measured distribution of rewards. From a family of animal trainers, Armand Grüss managed to get his cat to move along a plank and through a hoop, like Nigloo and Branlotin during the Cabaret équestre et musical Zingaro at the end of the 1980s.

In the 19th century, when wild beasts entered the world of the circus, which was essentially devoted to horses, the clown Hermany already presented a group of trained cats. Half a century later, a Russian trainer dressed as a clown in the Petrouchka style presents himself as a clown in love with cats... Coachman at the head of a full carriage of tomcats or chef discovering pots filled with small animals that escape smoothly, he leads some soloists in small scenes where he acts opposite, and introduces others in more conventional exercises. On the whole, the group obeys him, which belies the belief in the cat's irreducible instinct for independence.