by Luc Boucris

At the circus there is neither décor, nor heterotopia - the juxtaposition "in a single real place [of] several spaces, and several sites, which are themselves incompatible. 1" It is not without good reason that Pascal Jacob notes: "We have to admit that stage design, in the theatrical sense of the term, is reduced to its most simple form of expression [here]. 2"

And to tell the truth, when you look at circus show credits, you will not often see the stage designer credited as such.

However, several indicators show that stage design has become a necessary concept. Emmanuel Wallon notes, for example that "circus artists have become both poets and strongmen, stage designers as well as clowns, actors as well as lion tamers. 3" In the foreword to the same work, Jean-Pierre Angrémy pays the same type of tribute to this discipline when he writes that the clown "is at once the stage designer, gagman, musician, juggler, and funambulist, etc. for his act. 4"

François Cervantes puts stage designer in the credits of his shows, taking on the role5 as he does that of director. Philippe Goudard and Maripaule B. state that they have collaborated with a stage designer, Gilles Lambert6, in their credits. In fact one can feel that recently, stage designers are increasingly called upon, as seen, in one of many examples, in the collaboration between the clown Nikolaus, and Raymond Sarti7.

"Inured to an aesthetic reflexion that drives actor-spectator relations into a corner, aware that there is more than just a frontal relation, I experimented with all sorts of new forms of stage design… The art of the actor had to find new resonance, and the stage image needed simultaneously reinventing. And in particular, by using stage designs that questioned the bi-polar axis in the dramatic face-to-face of the box à l'italienne, everything had to be redesigned: the actor at the heart of the image, exposed to the eyes of the audience, and placed at the epicentre of all energy, the story was once again initiated by him. It has been noted that all these questions express the problematic of the circus artist." Gilles Lambert, in a letter to Maripaule B.

Questioning the space

It is the result of a double transformation/revolution: that of the circus itself and that of stage design. Whether at the very heart of the four fundamental disciplines (object manipulation, acrobatics, dressage or clowning), at the intersection of, or via various hybrid forms (with dance, theatre, the plastic arts etc.), the circus decided to look at the question of its space. As for stage design, it actually reappeared, at least in the vocabulary, at the turn of the 20th century, first in theatres, then diversifying from this theatrical anchor, as it was impossible to stick to a traditional décor of what was essentially a painted canvas, and it became urgent to address the issue of the space in a more global and complex way.

The question of the big top, which leads us to architecture, provides an excellent starting point to this dual problematic. Let us note, firstly, Pascal Jacob in the article quoted above, who says that with "the ring, the crimson curtain, that poles and the bench […] is the expression of an "accepted" stage design." Which means that he implements and epitomizes a type of stage design, a state of mind and a relation with the audience: risky stage designs (confronting the vertical dimension, confronting the audience without a protective backrest), the fairground spirit and a festive and conniving relation with the audience, whom the ring invites to gather together in public.

Let us also note that all of this is in no way exclusive to the big top, and that the very claim to the right for frontal performance is the perfect illustration of this crisis of the space, which is decisive (and so productive) in modern and contemporary performing arts.

However, it is not surprising that the big top retains this power of attraction and this imaginary force, which Aurélien Bory, founder of the Compagnie 111, explores in his show Géométrie de Caoutchouc (2011), in which he wanted to "make a sort of study of this space. 8" To do so, he took "as a décor a reduced sized replica of a big top" in which the show was held. Responding to questions, he said, among other things, that the big top was a place filled with promise. He added that his story reflected the skene of Greek theatre – the word means "tent." In short, he illustrated its richness in terms of stage design.

Dramatic art, Dramatic arts

For in addition to questioning our relation with space, the essence of the aesthetic issue set by the circus/stage design relationship is this: on the one hand, we need to find a place for this audacious dramatic art, which is a defining element of the circus identity (see Meyerhold9 for example), and on the other hand, enriching this dramatic art by going beyond a pure and simple admiration of skill.

With Quidam (1996), the Cirque du Soleil illustrated this aesthetic approach in a very convincing way. A steel arch straddled the stage, enabling acrobats and material to get to the top of the cupola. It evoked a place where the "anonymous"- or the quidam, meet. The system was computer-managed. The spectacular excess set in motion enabled the Cirque to Soleil to step up its acrobatic prowess through technological prowess, which was no longer questioned.

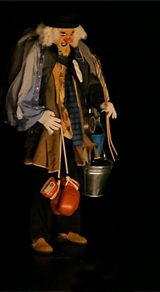

Almost opposing terms are required to describe Carnages (2013) by the Cie l’Entreprise/François Cervantes. Here, the clowns' audacity stems from Entrées clownesques by Tristan Rémy. Although derisory, their audacity is as excessive as the previous example, but is existential and therefore of an entirely different nature. It leads them to bravely confront the (fictionally) disaffected theatre in which they have taken refuge, and to build nothing less than a château, using cardboard boxes for this stage design. This château is fragile and comic of course, and temporary as it only lasts for a brief moment in the show, but it reveals that, in spite of the decay in which they are tangled, these clowns will never give up, and bounce back from one situation to the next, until they reach a comic, moving and poetic Olympia.

Catalysts for creation and relation

With relation to apparatus in particular, stage design finds favourable and significant grounds for expression, through various modalities.

For In vitro 09 (2009), Archaos implemented a structure which simultaneously enabled the apparatus to be rigged, became an apparatus itself, and was established in the show's message by developing a polysemic spatial metaphor ( a laboratory, a zoo construction, etc.), while evoking a big top. In this way, it was established, in its own right, in Archaos' global project: a desire for aesthetic, social and political resonance with its era, and a desire for an approach to the circus via an ambitious exploration of creating "universes to build," according to a statement on their website.

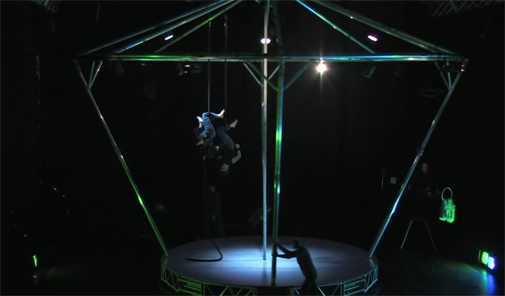

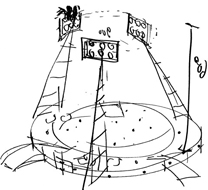

The stage designer Goury's proposal for Du Goudron et des plumes (2010) by MPTA

– Mains Pieds et la Tête Aussi –, and Mathurin Bolze, acted as a creative driving force and a provocation to action. It was a suspended platform that moved three ways: generally horizontal, it could be positioned on a diagonal, thereby putting the "acrobat-characters" on it, in a particularly unstable position. This giant apparatus was in turns the ceiling, a mobile stage, and a wildly fluctuating device forcing performers to adapt to its relentless movement. It carried the audience away in a mobile dream that was also rife with questions.

Finally, we should not neglect the material and subjective effects of stage design on spectators and audience they constitute throughout the show. A dynamic approach to the notion of the audience is, indeed, essential in understanding the aesthetic function of stage design.

Cirque Nu's light structure produces a level of concentration that creates or reinforces the sentiment of shared privacy for everyone. The mechanism of the "Arts Sauts," which placed the audience on deck chairs and positioned the acrobats 12 metres up in the air made the audience doubly grateful, owing both to the welcome and to the beautiful metaphor for an achieved ideal, suggested by the acrobats' flights. The rhythm established by the machine in Du Goudron et des plumes led to a feeling of empathy among the audience that enabled them to physically feel that only unfailing solidarity enabled them to face up to it. The apparatus, and even more so the big top, which collapses at the very end of Nikolaus Holz's show, which runs counter its title, Tout est bien !, paradoxically brings them back down to earth.

Between stage design and the circus show, an active collaboration takes place, for the space, far from being a simple container, fulfils a decisive function whether at the time of creation, or the time of performance.

1. Michel Foucault "Des espaces autres," in Architecture, mouvement, continuité, n° 5, Dits et écrits, 1984.

2. Pascal Jacob, "La victoire de la 3e dimension," in Arts de la piste, p. 18, Paris, October 2004.

3. E. Wallon, in the introduction to the collective work Le Cirque au risque de l’art (dir. E. Wallon), Actes Sud, Papiers, 2002, p. 14.

4. Ibid, p. 8.

5. By sharing this responsibility with the technical team. It provides an opportunity to emphasise that stage design is an invitation to create close links between the technical and the aesthetic.

6. Particularly significant in this collaboration are the stage designs created for Motusse et Paillasse – Clowns (1984), Le cirque intérieur (1986) and Cirque Nu (1995), used again in À corps et à cris (2002).

7. For Tout est bien, catastrophe et bouleversement, 2012.

8. The following quotations are all taken from an interview with Aurélien Bory by Manuel Piolat Soleymat in April 2011.

9. In particular in a text entitled "Vive le jongleur !", published in Echo du cirque n° 3, in August 1917, translated by Béatrice Picon-Vallin for Du cirque au théâtre, a volume in the Théâtre années vingt, l’Age d’homme collection, 1983.