Banques and saltimbanques

by Marika Maymard

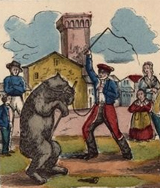

The intoxicating perfume of mystery and adventure offered by the traveling community of jugglers, wandering entertainers, acrobats, animal trainers, who go from castle courtyards to liturgical festivals – feira – has always inspired poets, storytellers and painters. Hitting the fairgrounds where merchants set up their stalls and set up their boxes, they are "fairground visitors", foreigners, literally those who come from elsewhere. From Ghent to Beaucaire, from Cambridge to Provins or London's Bartolomew Fair, from Frankfurt am Main to Place Vendôme in Paris, where the Foire Saint-Ovide was created in 1665, they crossed bridges and tolls, paying their dues with some "trick" performed by their animal or some juggling pass. It was therefore literally known as "monkey money".

In the 19th century, with the birth of the fairgrounds, these travellers brought know-how, languages and extraordinary characters into the city and the imaginations of the local residents, which would come together to supply the "banque" and, at the same time, the circus. A colourful, moving, thundering world, built around a few boards, il banco in Italian, a stage where we play the farce and from where we jump – saltare. These street performers ('saltimbancos') from all walks of life, from all backgrounds, whether they are setting up a stand, a wrestler's hut, a fairground theatre, an "umbrella" deployed over a sandbox or a menagerie several dozen metres long, are all from one same big family: the circus entertainers known as 'banquistes'.

"I went to the gingerbread fair the other night. Of all the public fairs, it is the one I prefer, with the exception of 15 August. There, arranged in a circle, camped in their caravans and huts, you see a whole army of acrobats – a strange, ancient race that attracts me as all those who flounder in struggle and adventure do"

Jules Vallès, La Rue, Paris, 1866.

The term saltimbanques refers to those who practice a profession based on performance, the term banquistes indicates that they belong to a common social body, a form of symbolic guild or brotherhood, with its rules, its ethics, a form of solidarity despite the adversity (contre-carre), this fierce competition inherent to the venture devoted to amassing the greatest profit in a limited time. They form the same family, but with its limits: people with important jobs do not mix with the people from the circus industry (entre-sorts) or the street entertainers. There are two distinct types of banques.

The small banque

The small banque groups together activities with multiple facets, which are certainly creative, improbable, even, until they become overwhelmingly stunning. Artists who work outdoor in the open air (en placarde), offer their performances on the edge of the fairs. Barkers, rope dancers, acrobats, conjurers, jugglers, hercules, musicians accompanied by the marmot of the little Savoyard or the papion monkey of the organ grinder, their luggage consists of a rug and a set of accessories, and the street is their only scenery. But, already, they play in a circle, formed by the audience.

In all the major cities, fairgrounds, Anglo-Saxon fairs, display on banners or paintings painted on facades, the curiosities offered to the eager crowds, domestic or commercial employees, workers, soldiers on leave... and aristocrats who came to slum it and loosen up. Along the dense fair aisles, the entresorts line up, these huts in which one enters at one end where a cashier in a black dress and a glossy tiara collects all the money, and from which one emerges at the end of a corridor or the arena hidden behind the canvas.

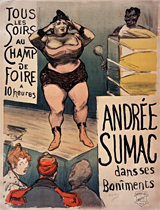

Anything can be displayed: animal or human monsters, whether natural or manufactured, living or made in wax, optical phenomena with appearances, disappearances, heads placed on dishes, dislocated or pierced fakirs, calculating animals, masterpieces reconstructed with extras wearing poor costumes... Canvas huts present curious animals like the armadillo and of course, the scary wild man, Satou or Divio in fairground language, pasted with walnut stain and fed a variety of fresh live pigeons. Some African or Hindu orchestra's accents pierce the ambient cacophony of the parades, small demonstrations commented by a blustering clown. The Olympic spirit exalts beauty and physical strength and guarantees the success of wrestling arenas. From the audience, the baron pushed the brave amateur to grab the glove to compete against the female colossus or against Ambroise Marseille's men, lined up in a parade.

The big banque

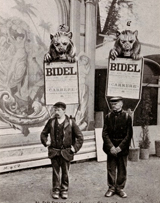

This somewhat arrogant term brings together the bank's aristocrats, its major industrial owners of menageries and fairground circuses, who present considerable establishments and collections of wild animals at major festivals. The names Wombwell and Bostock for the Anglo-Saxons, Pezon, Bidel, Laurent, Marck, Amar and Bouglione in France, Krone in Germany, founders and directors of imposing "pits", accelerated, from the period between the two world wars onward, the change in the spectacular architecture of the circus.

The equestrian circus presented in stable circuses or semi-constructed wooden circuses until the 20th century is over. From now on, it must share its facilities and its ring with great attractions such as cage entrances provided by large groups of wild animals. The development of the big top, the apparatus behind the great acrobatic acts and the clowns groups that that we simply can't get enough of, changed the image and representation of the post-war circus.

The influence of the other banque

The term "banque" sounds like a cash register, it evokes the economy of the fair. From the earthenware pot hidden under the family bed to the washing machine, the makeshift "safes" that collect the fairground revenues do not always cross the bankers' path. This means that levies, often fatal to the company, can be used to pay various fees and taxes. Many authors relay the complaints of fairground workers who denounce their excesses and, in France, the system of auctioning sites which favours the richest fairground industrialists. The high cost of transporting heavy convoys and, during the world conflicts of the 20th century, the near cessation of operations, animals stored in zoos or eaten, had a profound impact on the landscape of the fair and paved the way for the installation of new rides.

1. See Dr Frances Teague, The Curious history of "Bartholomew Fair", Édition : Lewisburg, N.J. : Bucknell university press ; London ; Toronto : Associated university presses, 1985.