by Alexandre Pich

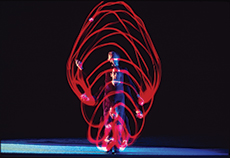

Graphic manipulation is the art of drawing in space some forms, trajectories and mechanisms, within a writing process with the body and the object. It involves figurative or abstract image-type characters borrowed from a vocabulary common to the public and the artist and arranges them one after the other to compose a scene, a journey or a story.

Multiple influences

In the environment of rituals and rites of passage, the gestures and costumes that transform the religious man do not seem to be exploited for graphic purposes, except perhaps the hoop dance by American Indians "invented" by a manitou, Pukawiss1 who proposes a series of very geometric figures composed by 1 to 18 hoops loaded with figurative and mystical meanings.

The world of armies and martial arts is marked by the manipulations of weapons or emblems characterised by the dexterity, speed of execution and harmony of spectacular overall scenes, such as flag throwing in Italy, used by Cirque du Soleil in Zarkana, for example. Some manoeuvres or parades involve a very graphic collective work that creates shapes, waves, splits, movements of rigid, perfectly designed blocks.

In the world of dance, Loïe Fuller at the end of the 19th century, made her sails twirl over themes and according to a dynamic of changing movements thanks to projections of patterns and colours. In 1915, Dave and Max Fleischer invented the rotoscopy, a cinematographic technique that emphasises the contours of characters in motion. A century later, the Japanese Masahiko Sato and the Euphrates group created a rotoscope ballet on screen where the evolutions of the ballerina are materialised by virtual, straight or scroll-shaped, intermittent lines.

Kinetic art, whose foundations laid in 1920 invoke the notions of construction, mechanisms and optical phenomena, developed in 1960. It proclaims the beauty of movement and for some works, all that is missing is the intervention of the body to be able to talk about graphic manipulation.

Cubism, Futurism, then Constructivism and Bauhaus actively exploit geometric and abstract forms and the movement generated. Their environment and aesthetic vision extend to the field of the living arts by offering the first performances and staged productions. The emphasis is on the compositions in a space of forms and images related to the machine and its mechanisms, which interact to create an overall pictorial visual on stage. The sets are inspired by modern art, the scenography is movable and the bodies, dressed in geometric costumes, designed by creators such as the Delaunays, are often extended by objects, as in the work of Oskar Schlemmer (to whom the juggler Malte Peter paid tribute in 2015 in his composition L'homme en bois, presented at the Bauhaus in Dessau). However, it is difficult to talk about graphic writing that no futuristic manifesto claims.

The manipulation of clubs through time and around the planet

In Persia, over the centuries, Pahlavani wrestlers have used two war clubs for their daily physical training. The objects and the principle of manipulation spread to India, then, brought back to Europe by British settlers at the beginning of the 19th century, they interested a wider public. What until then had only served as good physical conditioning was then adorned with notions of aesthetics, geometry of manipulation and pleasure. In 1900, George W. Patterson of Chicago customised Indian clubs with light bulbs and presented sequences of figures in the dark for a few seconds, which he photographed as long exposures photos. Geometric shapes then emerge in space: graphic manipulation is born!

The practice gradually spread and in the early 2000s encouraged the anti-spin theory and the discovery of new figures. Equivalent to siteswap for rotating objects, this theory allows not only to systematise the possibilities of rotating movements but also to "clean" the figures of non-geometric imperfections. This theory can be applied to all rotating objects: clubs, batons and sticks, hoops or Buugengs. Essential tool for graphic manipulation, it makes it possible to carry out very precise trajectories, circular, linear, etc.

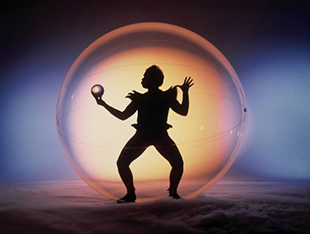

But the real graphic revolution was due to Michael Moschen who, in the 1980s, created graphic manipulation routines for hoops, sticks, S-staffs (Buugengs), large tubes and transparent acrylic balls. Using the fixed-point technique where the object as a whole or a point of the object remains static in space while the body holding it moves, Michael Moschen levitates his objects and gives them very precise intentional trajectories. It offers a refined aesthetic of geometric shapes in sequence following a set of visual logics... which are graphics.

Subsequently, Jochen Schell with his rings and spinning tops, Jive Faury with his three clubs, then his cane and finally his strings, Emanuele Marongiu with his crystal balls, create graphic manipulation routines. The latter, a member of a London community, contributed in the mid-1990s with, among others, John Blanchard, Dimitri Ogden and Dugh, to the spread of graphic manipulation through juggling conventions and the Internet. These small communities are merging into a new movement called flow, which began in the United States in the early 2010's, around the disciplines of objects rotations, including flaming objects. The flow movement seeks well-being and serenity in practice. But it is open to graphic manipulation and welcomes new objects such as the Buugengs in the early 2000s, the pairs of iso batons and the pairs of "eight" – eight-rings. In parallel, collectives were formed at the origin of the first purely graphic manipulation shows such as Très très très by the Piryokopi collective.

In full evolution, graphic manipulation is a "performance" in the sense that it involves the body, the space and also time. It can be described as kinetic because it highlights the beauty of movement. Finally, it creates a vocabulary of forms and movement, which makes it unique.